'Bavarian Gentians' by D.H. Lawrence

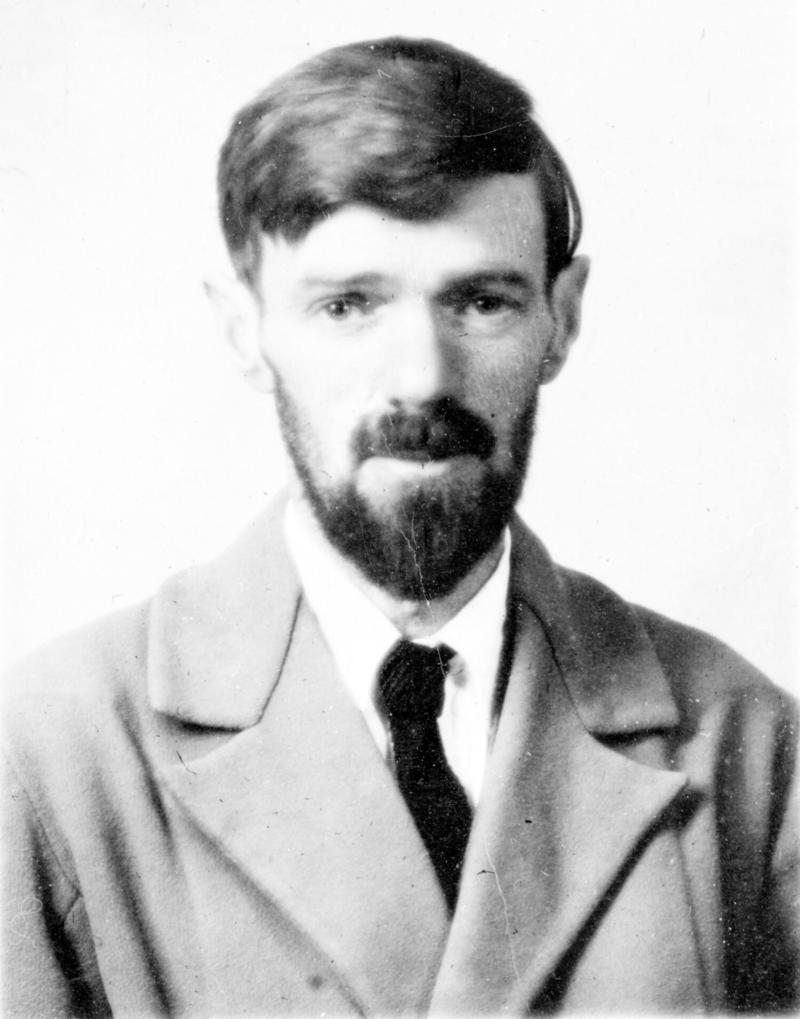

Passport photograph of the British author D. H. Lawrence, enclosed in a letter to Bernard Falk (1882–1960), dated 24 February 1929

D. H. Lawrence Collection, General Collection. Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

David Herbert Lawrence (1885-1930) was one of the most original and important writers of the twentieth century. He is best known for his novels, particularly for their celebration of the body as an antidote to modernity and its discontents, but he wrote some remarkable poetry throughout his life, including Birds, Beasts and Flowers (1923) and the posthumously published Last Poems (1932), where ‘Bavarian Gentians’ appears.

How does a writer who has obsessively celebrated the joy of being alive – ‘the shimmering protoplasm of life’ – imagine his imminent death? In ‘Bavarian Gentians’, D.H. Lawrence does precisely that. By 1925, Lawrence knew he had tuberculosis and, by the time he started on the poem, he knew he was dying. ‘Bavarian Gentians’ belongs to a series of poems written on two notebooks that bear physical traces, scholars claim, of his final illness as Lawrence, like John Keats, coughed up blood; they were published after his death as Last Poems (1932). The poem remains as remarkable an achievement in the history of twentieth-century verse as it is in his own oeuvre.

‘Bavarian Gentians’ was begun in September 1929 when Lawrence was recuperating in the Bavarian Alps. His wife Frieda overheard him muttering to himself: ‘I can’t die, I can’t die, I hate them too much’. His sister remembers how ‘Lorenzo lay in a bare room with some pale blue autumn gentians as the only furnishing’. The poem bears witness to the process by which, in course of nineteen lines, these ‘autumn gentians’ metamorphose into the blazing ‘torches of darkness’. They illuminate in the process the worlds of biography and myth and poetic influence as Lawrence imagines his death as an underground descent.

Sound, vision and touch are fused and confused, with the long, undulating lines with their rhythmic repetition, variation and assonance working under the guard of our consciousness. If ‘soft September’ brings in the autumnal Keats, can Walt Whitman, whom Lawrence called ‘that great poet, of the end of life’ be far behind? In Whitman’s poem, ‘Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking’, the sea whispers to the poet ‘the low and delicious word, death’: ‘And again death, death, death, death’. In ‘Bavarian Gentians’, the dying Lawrence can only say ‘dark’. Having celebrated the dark gods throughout his writing, from Sons and Lovers to ‘Twilight in Italy’ to ‘The Blind Man’, he would now reach for his favourite word, not just as an image or idea or sound, but as a charm or relic, repeating it some seventeen times. The ‘darker and darker’ stairs down which we are led is a sound-spiral, an example of what T.S. Eliot would later call the ‘auditory imagination’ in poetry. Reiteration with Lawrence is not just intensification but also transformation. The darkness thickens and becomes palpable, just as the ‘torch-like (‘sheaf-like’ in the draft) flowers change, from the immediacy of ‘Reach me a gentian, give me a torch’ to the twice-repeated metaphor (‘torch-flower’) to the visual paradox (‘torches of darkness’) at the heart of the poem.

The poem brings together different aspects of Lawrence’s life and art. Lawrence would have remembered his actual descent, in 1927, into the Etruscan tombs where ‘lamps … guided the way’, recorded in Etruscan Places (published posthumously in 1932). At a psychological level, the descent would have been an imaginative visitation of the underground world of his coal-miner father (as in his 1928 painting ‘Accident in the Mine’). The ‘dark blue’ of the gentians would have reminded him of his mother’s eyes. ‘My mother had blue eyes,/They seemed to grow darker as she came to the edge of death’, he wrote in his elegy, 'Bereavement'.

In a cancelled draft of the poem, the mother is linked to Persephone. Is Lawrence, in imagining Persephone in ‘arms Plutonic’, revisiting the primal (sexual) scene? There was also the more immediate, painful context of Lawrence’s impotence from 1926 and his wife Frieda periodically abandoning him for the arms of the young Italian officer Angelo Ravagli. The great irony was that Lawrence had staked everything on the cult of the body and his own body had miserably failed him. Is the great sexual crisis in the life of this prophet of love here being turned into a narrative of sexual violence (‘pierces her once more’) or is there a masochistic jouissance (pleasure) as Lawrence, Persephone-like, imagines himself being ravished by his dark god? Like much of great poetry, ‘Bavarian Gentians’ teases us with various possibilities, refusing to provide any answers and instead gathering us into the spell of the sensuous.

—Santanu Das

'Bavarian Gentians'

Not every man has gentians in his house

in Soft September, at slow, sad Michaelmas.

Bavarian gentians, big and dark, only dark

darkening the day-time, torch-like with the

smoking blueness of Pluto’s gloom,

ribbed and torch-like, with their blaze of darkness

spread blue

down flattening into points, flattened under the

sweep of white day

torch-flower of the blue-smoking darkness,

Pluto’s dark-blue daze,

black lamps from the halls of Dis, burning

dark blue,

giving off darkness, blue darkness, as Demeter’s

pale lamps give off light,

lead me then, lead the way.

Reach me a gentian, give me a torch!

let me guide myself with the blue, forked torch

of this flower

down the darker and darker stairs, where blue is

darkened on blueness.

even where Persephone goes, just now, from the

frosted September

to the sightless realm where darkness is awake

upon the dark

and Persephone herself is but a voice

or a darkness invisible enfolded in the deeper dark

of the arms Plutonic, and pierced with the passion

of dense gloom,

among the splendour of torches of darkness,

shedding darkness on the lost bride and

her groom.

Some themes and questions to consider

-

the role of sound

-

the relationship between death and desire

-

the relationship between myth and biography

Full text

The poem is easily found online; you can hear Glyn Maxwell reading it, with a short introduction, here. And here’s another reading, by Anthony Burgess.

There is some controversy about the ‘final’ version of the poem. The heavily revised manuscripts are held at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Centre, University of Texas at Austin.

The version provided here is the one that appears in the posthumous Last Poems (1932) edited by Richard Aldington and Giuseppe Orioli. Also see Christopher Pollnitz, D.H.Lawrence: The Poems Volume 2 (Cambridge, 2013) (The Cambridge Edition of the Works of D.H.Lawrence), which is the definitive edition of Lawrence’s poems.

The collection, Birds, Beasts and Flowers, along with a number of Lawrence's other collections and novels is available via Project Gutenberg.

The life and work of D.H. Lawrence

A biographical introduction to Lawrence from Poets.org with links to further poems.

Women in Love

A British Library introduction to Women in Love by Neil Roberts, also introducing Lawrence as a novelist.

The Ship of Death

An analysis of Lawrence's last poems by Sam Buntz on the literary blog, The Muted Trumpet.

Lawrence and the Senses

Santanu Das, writing for the British Academy, discusses the poem in greater detail alongside its manuscript version.

D.H. Lawrence on Great Writers Inspire

A series of Great Writers Inspire podcasts discussing Lawrence's context and influences.

D.H. Lawrence: a postcolonial writer?

In this podcast Peter McDonald draws on the work of Indian novelist and literary critic, Amit Chaudhuri, to consider D.H. Lawrence in the context of post/colonial writing.

Modernism

In this Great Writers Inspire article, Rebecca Beasley places Lawrence with a number of other writers in the wider context of the modernist movement.

About the Contributor

Santanu Das is Senior Research Fellow and Professor of Modern Literature and Culture at All Souls College, University of Oxford. He is the author of Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature (2006) and India, Empire and First World War Culture: Writings, Images, and Songs (2018) and the editor of Race, Empire and First World War Writing (2008) and Cambridge Companion to the Poetry of the First World War (2014). He is currently editing the Oxford Book of First World War Empire Writing and working on a collection of essays provisionally titled Forms of Experience.