Imagining Queer Ecologies

‘Imagining Queer Ecologies’ was a one-day, online symposium, co-organised by Drs Laura E. Ludtke (she/her), Joshua Phillips (he/him), and Martina Astrid Rodda (they/them) and co-hosted by the Faculty of English at the University of Oxford and the British Society for Literature and Science (BSLS), that took place in December 2023. With over 200 registered attendees from five continents and presenters from around the world, the symposium foregrounded the diverse and often collaborative work of researchers from around the world and brought together postgraduate and early career researchers (PGR/ECR) working at the intersection of literary studies, queer studies, and the environmental humanities. The BSLS funds and supports an annual winter symposium organised by PGRs and ECRs around emerging and urgent themes in the field of literature and science (broadly conceived); over the past few years, themes addressed have included: ‘The Subterranean Anthropocene’, ‘Decolonising Literature and Science’, and ‘Extinctions and Rebellions’.

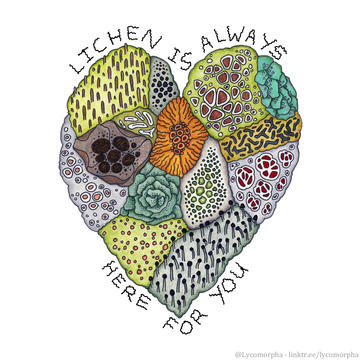

In life as in art, may we all be a little more lichen.

Queer ecology is an emerging concept in queer theory and the environmental humanities that has been adopted in scholarship across the sciences, social sciences, and arts and humanities to address questions of community, biodiversity, organicism, and posthumanism. It offers a potent critical and interpretive approach to exploring the intimacies and interdependencies of literature and science, medicine, and technology. As such, queer ecology represents a potent framework for addressing the intersectionality of not only what is natural, but also what is queer. It can also serve as a theoretical framework to challenge what Barri J. Gold, in her 2021 monograph Energy, Ecocriticism, and Nineteenth Century Fiction: Novel Ecologies, identifies as the ‘concept of nature’ developed across the nineteenth century within and beyond the literary and scientific ecosystems in which this concept develops. For instance, how might a consideration of queer ecology together with literature and science encourage us, as Gold exhorts us, to reconsider ‘the dominant way of thinking about what we call our environment, imagining nature as the stage set against which we act and which is ours to do with what we please’?

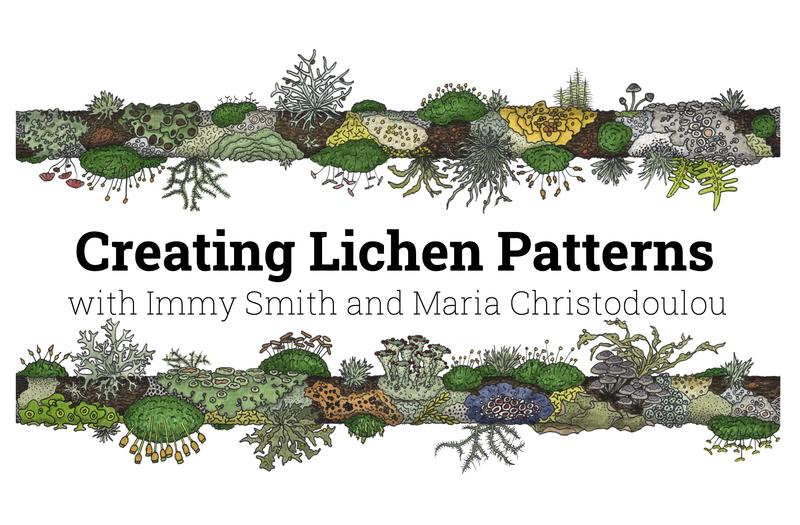

[Image © Immy Smith/@Lycomorpha]

‘Imagining Queer Ecologies’ fostered conversations about a wide range of topics relevant to queer ecology across the field of literature and science, medicine, and technology. It also extended Gold’s invitation to reconsider ‘nature as nature’ to imagining ways of relating to, engaging with, knowing, and representing the environment that do not reproduce the established anthropocentric, technocapitalist, petrocultural, heteronormative, cisgender, ableist, colonial models. For this reason, the symposium began with ‘Creating Lichen Patterns’, a doodle workshop devised and led by Immy Smith (visual artist & head of pencil hoarding) and Dr Maria Christodoulou (biostatistician & keeper of random numbers), exploring how the non-binary nature of lichen symbiotic communities helps us to challenge what we think we know, and to see beyond artificially imposed categories and relationships.

In this blog post, reflecting on one of the sessions of the ‘Imagining Queer Ecologies’ symposium, we will introduce you to the principles of queer ecology and how to imagine them through the ‘wonderfully queer world of lichens’ in a series of drawing games Immy and Maria Christodoulou devised for the ‘Creating Lichen Patterns’ workshop and shared with their permission here (you can read the original on Immy’s website here). Creativity is at the heart of our vision of queer ecology and we felt it was important that everyone attending the symposium have the opportunity to explore and reconfigure their relationship with representing nature. The workshop activities Immy and Maria designed require no skills or specialist materials. All you need is a writing implement and a surface on which to draw.

Reference for the discussion of lichen biology: Evolutionary biology of lichen symbioses, Toby Spribille, Philipp Resl, Daniel E. Stanton, Gulnara Tagirdzhanova, New Phytologist 2022. Further references given as links in text.

Lichens are symbiotic communities that can grow almost anywhere. Although often considered slow-growing and unexciting, lichens have found ways to grow in the driest, hottest, and coldest reaches of this planet. They’ve remained viable after exposure to the vacuum of space via experiments on the International Space Station. They help land to recover after being damaged by industrial pollution, and can survive in conditions that sometimes seem impossibly toxic and harsh. Lichens do this by being cooperatives of different kinds of organism working together.

Task 1. Warm-up & warm down

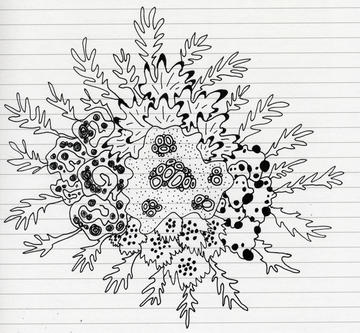

[Image © Immy Smith/@Lycomorpha]

This was the warm-up for anyone arriving early, and we used it as the warm-down while wrapping up and taking questions

- Roughly draw a pile of rocks taking up most of a page; perhaps 10-15 rocks is a nice number

- The rocks can be any shape, texture, or size; from small pebbles to large boulders that are rounded, angular, or jagged

- Imagine that patches of lichen, moss, liverworts, or other small life forms have grown on the rock pile over time; consider how they survive on the surface of the stone

- Doodle patches of life on the rocks in your pile; whether spotty or striped, smooth patches or fluffy tufts, make them as simple or twiddley as you like. Don’t worry too much about sticking neatly within one rock. It doesn’t matter if a lichen grows over multiple rocks, or a plant bumps into a liverwort, for example

Because of their cooperative nature, lichens have always been controversial. In the past, some scientists who believed in survival of the fittest, in competitive domination of one organism by another, were incredulous that species from different taxonomic branches of life would work together in this way. A new word – symbiosis – was coined to describe the way fungi and algae worked together in lichens, and thus could thrive in places where neither could flourish alone. This was the original lichen model; a species of fungus and one of alga made up a lichen.

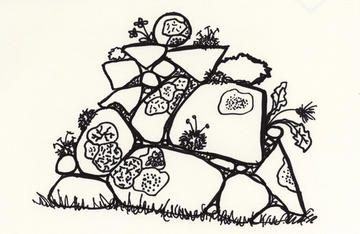

Task 2. Levelling game: terrible landscapes

In this game we ask you to draw an absolutely terrible landscape. The emphasis here is on drawing in a way we’re often told is ‘bad’, so your image doesn’t need to be accurate or tidy. Please draw as messily as you like during this activity (and for the rest of the workshop) – here’s an example from this game:

[Image © Immy Smith/@Lycomorpha]

We’re commonly taught that the only valid form of drawing is one that meets certain standards of ‘good’ or realistic, accurate representation. This is an artificial barrier to drawing as a fun, creative outlet. Children are generally happy to grab art materials and have fun, however ‘good’ or accurate the result. At some point many of us lose that glee, and our freedom to doodle for fun is squashed out of us. Drawing ‘terribly’ is a way to regain that freedom, and start un-squashing our creative flow

- Draw a frame for your landscape, preferable a wonky one. It can help to have boundaries to ignore/draw over if we’re trying to draw badly.

- Turn your page upside down. We will draw all the features of this landscape the wrong way up. This will help it look terrible when we flip it again.

- Take your pen/pencil in your non-dominant hand and spend 30 seconds drawing an upside down line of background hills or mountains.

- In the middle ground, we have trees. Put the tip of your pen on the paper; we’re going to draw trees without lifting it off the paper again. For 1 minute draw upside down trees across your landscape, without lifting up the pen between trees. Any kind of terrible tree or shrub is good.

- There is a river in the foreground of our upside-down landscape. Put your pen on the page and then look away from your paper. Spend a minute drawing a river flowing across your picture without looking back down at your page.

- For those feeling ambitious, spend the last minute drawing upside-down fish in your river, while keeping one eye (your dominant eye if you have one) shut.

We’ll time these steps, and at the end flip our drawings to what we’ll laughingly call the right way up and admire how terrible our landscapes are. Hold on to the spirit of drawing fun because there is no definitive one good way to draw in life, but especially not at this workshop.

[Image © Immy Smith/@Lycomorpha]

The thing about lichens is… They don’t care about human models, binaries, and boundaries.

It became clear in time that things were not that simple. A lichen could contain a cyanobacteria or an alga. Sometimes the same lichen could contain one or the other, depending on location and environmental conditions. We then realised some lichens could contain both an alga and a cyanobacteria at the same time. In the past decade or so, it has become clear that at least some lichens can contain a fungus, an alga, and… Another fungus too. From a very different taxonomic group. And then there were three. Whoops, there went that nice binary idea!

Lichens are very queer like that.

You can try out the other doodling activities which featured at the ‘Imagining Queer Ecologies Symposium’ on Immy’s Moths in a Human Suit website. The activities helped the symposium delegates delve into the principles of queer ecology, as detailed below, as well as giving them the opportunity to explore their own creativity.

Lichen teaches us to look differently and to see more. It says that it is possible for us to live outside the constraints and binaries some people want to place on us, that together we can grow over our perceived borders and push creative boundaries. We can be lichen-like and thrive in seemingly impossible conditions by helping each other to flourish.

Recent research in lichenology suggests that perhaps even four different organisms together form some lichen. Who knows if and when more may be observed. What are all these symbiotic partners doing in there? We don’t entirely know in most cases – and that’s a joy! Lichen research will likely change the way we think about symbiosis more and more. In fact, many people have begun thinking of lichens less as species and more as communities. Lichen has and continues to challenge what we think we know about the interrelationships between organisms that shape the world.

Whenever it seems that established scientific binaries that have held for hundreds of years don’t change, we might want to remember lichen. Toby Spribille, a scientist involved in research that has changed how we think about lichen, said “we can only ask questions that we have the imagination for.” To think of this another way; if we only ever look for two things, and only consider those two things to be a valid finding, we will only ever see the same two things.

Lichens don’t care about the arbitrary definitions humans have applied to them over time. They’re far too busy building colourful communities that can thrive in seemingly hostile places. In life as in art, may we all be a little more lichen.

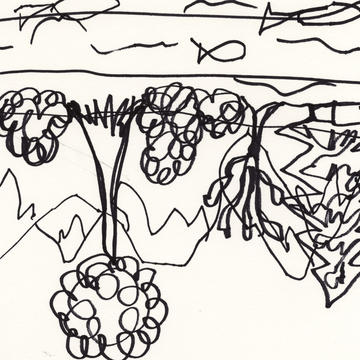

[Image © Immy Smith/@Lycomorpha]