Pandemics from Homer to Stephen King

Chelsea Haith, DPhil Candidate in Contemporary English Literature, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pandemics from Homer to Stephen King: what we can learn from literary history

Chelsea Haith, University of Oxford

From Homer’s Iliad and Boccaccio’s Decameron to Stephen King’s The Stand and Ling Ma’s Severance, stories about pandemics have – over the history of Western literature such as it is – offered much in the way of catharsis, ways of processing strong emotion, and political commentary on how human beings respond to public health crises.

Literature has a vital role to play in framing our responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is worth turning to some of these texts to better understand our reactions and how we might mitigate racism, xenophobia and ableism (discrimination against anyone with disabilities) in the narratives that surround the spread of this coronavirus.

Ranging from the classics to contemporary novels, this reading list of pandemic literature offers something in the way of an uncertain comfort, and a guide for what happens next.

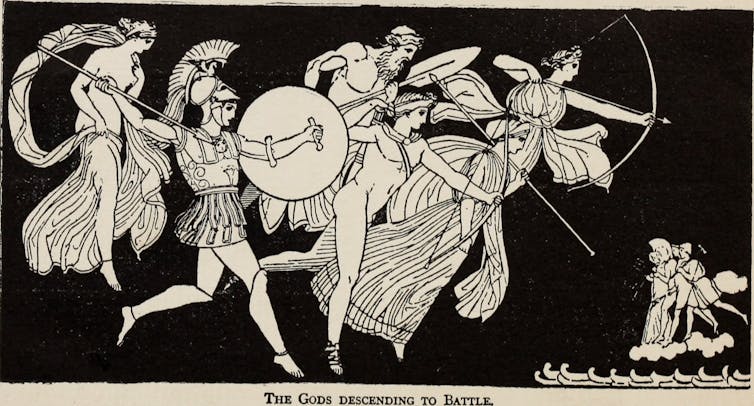

Homer’s Iliad, as the Cambridge classicist Mary Beard has reminded us, opens with a plague visited upon the Greek camp at Troy to punish the Greeks for Agamemnon’s enslavement of Chryseis. US academic Daniel R Blickman has argued that the drama of Agamemnon and Achilles’ quarrel “should not blind us to the role of the plague in setting the tone for what follows, nor, more importantly, in providing an ethical pattern which lies near the heart of the story”. In other words, The Iliad presents a narrative framing device of disaster that results from ill-judged behaviour on the part of all of the characters involved.

COVID-19 is certain to shake up economic systems and entrenched institutional processes, as we’re seeing with the shift towards remote learning in universities around the world, to give just one example. These texts give us an opportunity to think through how similar crises have been managed previously, as well as ideas about how we might structure our societies more equitably in their aftermath.

The Decameron (1353) by Giovanni Boccaccio, set during the Black Death, reveals the vital role of storytelling in a time of disaster. Ten people self-isolate in a villa outside Florence for two weeks during the Black Death. In the course of their isolation, the characters take turns to tell stories of morality, love, sexual politics, trade and power.

In this collection of novellas, storytelling functions as a method of discussing social structures and interaction during the earliest days of the Renaissance. The stories offer the listeners (and Boccaccio’s readers) ways through which to restructure their “normal” everyday lives, which have been suspended due to the epidemic.

Authority’s failure to respond

The normality of everyday life is also the focus of Mary Shelley’s apocalypse novel The Last Man (1826). Set in a futuristic Britain between the years 2070 and 2100, the novel – which was made into a movie in 2008 – details the life of Lionel Verney, who becomes the “last man” following a devastating global plague.

Shelley’s novel dwells on the value of friendship, and concludes with Verney accompanied on his wanderings by a sheep dog (a reminder that pets may be a source of comfort and stability in times of crisis). The novel is particularly scathing on the topic of institutional responses to the plague. It satirises revolutionary utopianism and the in-fighting that breaks out among surviving groups, before these also succumb.

Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Masque of the Red Death (1842) also depicts the failures of authority figures to adequately and humanely respond to such a disaster. The Red Death causes fatal bleeding from the pores. In response, Prince Prospero gathers a thousand courtiers into a secluded but luxurious abbey, welds the gates closed and hosts a masked ball:

The external world could take care of itself. In the meantime it was folly to grieve or to think. The prince had provided all the appliances of pleasure.

Poe details the sumptuous festivities, concluding with the incorporeal arrival of the Red Death as a human-like guest at the ball. The plague personified takes the prince’s life and then those of his courtiers:

And one by one dropped the revellers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel, and died each in the despairing posture of his fall.

Modern and contemporary literature

In the 20th century, Albert Camus’ The Plague (1942) and Stephen King’s The Stand (1978) brought readers’ attentions to the social implications of plague-like pandemics – particularly isolation and failures of the state to either contain the disease or moderate the ensuing panic. The self-isolation in Camus’ novel creates an anxious awareness of the value of human contact and relationships in the citizens of the plague-stricken Algerian city of Oran:

This drastic, clean-cut deprivation and our complete ignorance of what the future held in store had taken us unawares; we were unable to react against the mute appeal of presences, still so near and already so far, which haunted us daylong.

In King’s The Stand, a bioengineered superflu named “Project Blue” leaks out of an American military base. Pandemonium ensues. King recently stated on Twitter that COVID-19 is certainly not as serious as his fictional pandemic, urging the public to take reasonable precautions.

Similarly, in his 2016 novel Fever, South African author Deon Meyer details the apocalyptic fallout of a weaponised, bioengineered virus that results in enclaves of survivors besieging one another for resources.

In Severance (2018), Ling Ma provides a contemporary take on the zombie novel as the fictional “Shen Fever” renders people repetitive automatons until their deaths. In a thinly veiled metaphor for the capitalist cog-in-the-machine, the protagonist Candace drifts daily in to her place of work in a future New York that is slowly falling apart. She eventually joins a survival group, assimilating culturally and morally to their violent attitudes towards the zombies, “embodying the atomisation of late-capitalist humans in a society stripped to its bones”, as reviewer Jiayang Fang suggests.

For some the end has already come

Consider also that “indigenous futurisms” – a term coined by First Nations cultural and race studies theorist Grace L Dillon to refer to speculative fictions by indigenous peoples and writers of colour such as NK Jemisin’s Broken Earth series, Claire G. Coleman’s Terra Nullius, and Carmen Maria Machado’s short story Inventory – have long since treated colonialism and the diseases spread by the colonisers as the source of what is currently experienced as an ongoing apocalypse. For many people in formerly colonised places, the apocalypse has already come – pandemics (both literal and metaphorical) have already obliterated their populations.

The catharsis that some of the above-mentioned texts may offer is troubled by the realities of pandemic and apocalypse conditions depicted in much fiction by indigenous peoples. If we used our own likely forthcoming periods of self-isolation to theorise alternative social structures, to tell one another stories about how we live, what stories might we tell?

Chelsea Haith, DPhil Candidate in Contemporary English Literature, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()