‘of making manye bokis is noon ende’: Editing the Wycliffite Bible

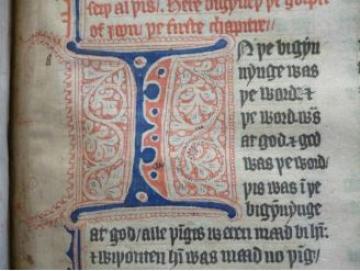

In the bigynnynge was the word... bodleian library, ms fairfax 1,1 f. 82r.

Readers of the first issue of Spotlight in August 2016 might remember a mention of the ‘Towards a New Edition of the Wycliffite Bible’ project, which is led by Dr Elizabeth Solopova

and also involves Professor Anne Hudson and a postdoctoral research assistant, Daniel Sawyer (me). The project’s goal is to begin re-editing the Wycliffite Bible (WB). This late-fourteenth century text, probably originating in Oxford, is the first complete translation of the Bible into English. It’s also the longest Middle English text and, by manuscript survival, the most successful English text before print. These last two facts go a long way to explaining why a new edition is needed and why the task is a big one! But what does working on this project mean, in a practical, day-to-day sense?

There are around 250 manuscript witnesses in total. A central core of these are, we think, most likely to be the key witnesses. Accessing the key manuscripts which are in Oxford is usually easy enough, but to read those which are elsewhere we’ve assembled a substantial library of facsimiles. A few manuscripts have been digitised and made available online in public facsimiles—from within Oxford itself, Christ Church and the Bodleian have put up Christ Church MS 145, for instance—and in some cases we have access to restricted digital facsimiles or sets of photographs, some of which we will be making publicly available. For other manuscripts we’re relying on our own photographs, digitised microfilms or, in extremis, physical microfilms. (To me, spooling up a microfilm in an analogue microfilm reader feels more archaic than opening a medieval manuscript—after all, a 600-year-old manuscript works, physically speaking, just like a book published in 2017!) Using these resources we’ve successfully collated the texts offered by most of our central witnesses.

While facsimiles are a great help, we do need to handle the manuscripts: some features of their construction can only be studied in person, and even the text itself isn’t always clear in photographs. The largest single concentration of copies is in Oxford, conveniently, but there are still many elsewhere, so the three of us have begun a series of research trips. Indeed, I’m writing this in a B&B on a wet and blustery evening in Dublin, where I’ve been consulting the manuscript copies of the Wycliffite Bible in Trinity College, which range from a copy which probably predates 1400 to an unusual Elizabethan manuscript of the New Testament: one of Shakespeare’s contemporaries was apparently willing to hand-copy a Bible translation which originated two centuries earlier. It’s a privilege to work on a topic which requires research travel like this, and there’s a certain excitement to be had in throwing a ruler, a magnifying glass and a few books in a bag and setting out for a foreign library. Or at least that’s what I tell myself when awaiting a bus to the airport in the small hours of the morning. But we are also (I promise) thinking hard about how to make these trips as efficient as possible, and we hope that our findings will permanently advance scholarship.

Meanwhile, we’re also involved in prototyping work for our open-access digital edition of the Wycliffite Bible. This digital edition will be designed to expand over time, and so allow us and others to carry forward the task of reediting the whole Wycliffite Bible beyond the end of our project, in a less intense but (we hope) much longer-term way. Project members from the university’s IT Services have designed a provisional interface for the digital edition and we have a prototype version of just two chapters available at https://wycliffite-bible.english.ox.ac.uk.

Finally, we have secured a substantial grant from Oxford’s John Fell Fund for a closely-related year-long research project on the Wycliffite Old Testament Lectionary. The Lectionary is a valuable, underexamined text, and deserves an edition in its own right. It’s also closely related to the Wycliffite Bible, and we suspect that the process of editing it might reveal more about the Wycliffite Bible’s text at a very early stage in the translation process. Cosima Gillhammer has joined us to carry out this adjacent editorial work.

Dr Daniel Sawyer

Postdoctoral Research Assistant, Towards a New Edition of the Wycliffite Bible