Spotlight on Research: Utopia Now

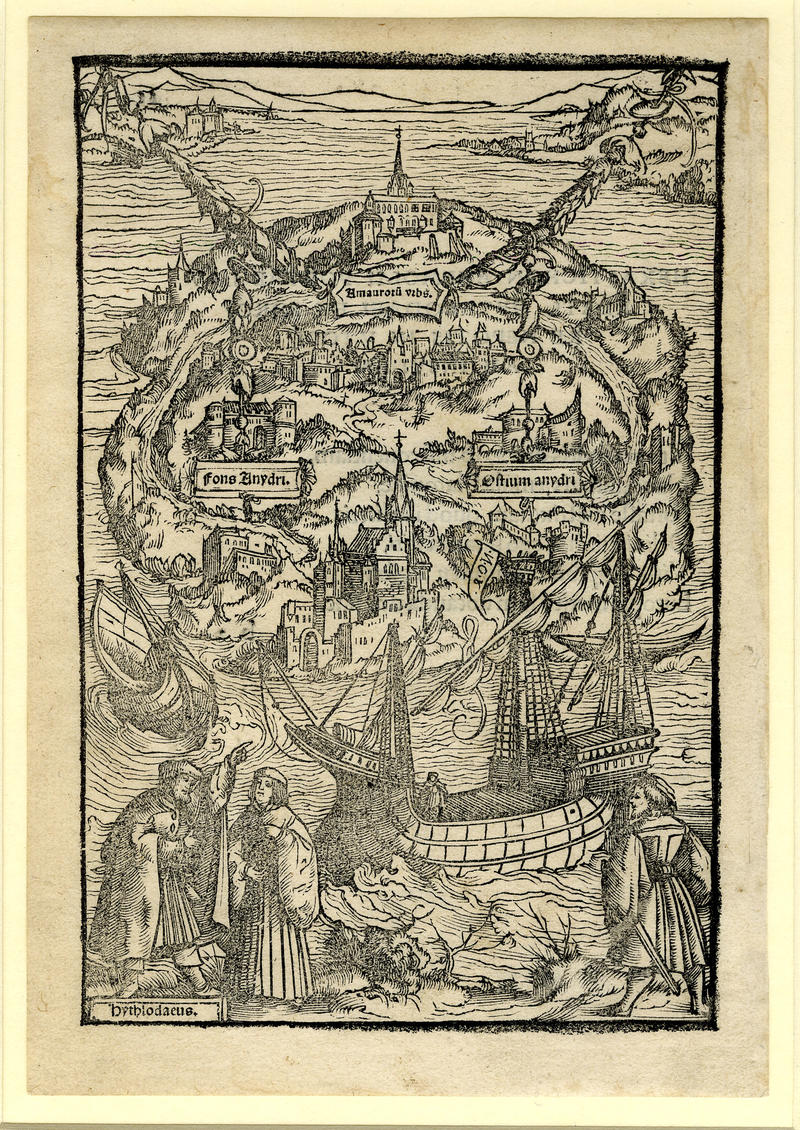

Illustration used on p. 12 of Thomas More, 'De optimo reip. statu deque nova insula Utopia...', Basel: J. Froben, March 1518 © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Our own time is arguably characterised by a range of crises which, in their range and magnitude, seem to presage the end of a period of modernity.

It is the case that every contemporary moment feels like a crisis to those living through it, to those who are its contemporaries. Crisis is perhaps one of the only historical constants. This is a truth that the schoolboy Marshall stumbles across in Julian Barnes’s 2011 novel The Sense of an Ending. A history teacher at the opening of that novel asks his class to reflect on the ‘reign of Henry VIII’, to offer a ‘characterisation of the age’. Met with silence, the teacher picks on Marshall – a ‘cautious know-nothing who lacked the inventiveness of true ignorance’. ‘Well, Marshall. How would you describe Henry VII’s reign?’. Marshall’s answer: ‘There was unrest, sir’. ‘Would you perhaps care to elaborate’, the teacher says. ‘Marshall nodded slow assent, thought a little longer, and decided it was no time for caution. “I’d say there was great unrest, sir”’.

Every age, to echo the title of Barnes’s novel, has its own sense of an ending. But as, for Tolstoy, all unhappy families are unhappy in their own way, so all periods experience their crises differently. And for us contemporaries, great unrest comes in the form of a particular kind of omni-crisis. The weakened legitimacy of liberal democracies in Europe and North America since the turn of the century have led to the current geopolitical crisis. Related to this weakening of the democratic sphere, we have seen a growing info-technological crisis, in which emerging forms of virtuality and artificial intelligence transform social relations beyond recognition. And looming over these geopolitical and info-technological crises is the climate emergency, which requires us to recognise that the way in which we have dwelt on the planet is threatening to destroy it.

Given this omni-crisis, this sense that what Jürgen Habermas called the unfinished project of modernity has brought us to the brink of an apocalyptic ending, it might seem perverse to insist upon the continued relevance of utopian thinking. But the project in which I am currently involved – a season of events and collaborations running in the Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities over Autumn 2026, going by the name ‘Utopia Now’ – sets out from the premise that now is, precisely, a time in which utopian thinking and imagining becomes not only necessary but unavoidable.

This is because utopian thought forms have tended to emerge not as a reflection of political stability or hegemony, but in response to the perception that our mechanisms for representing our social and political being have faltered, or failed. Such failure is what the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci has in mind when he anatomises his own geopolitical crisis from his prison cell in 1930. ‘The crisis’ he writes in a line that has become talismanic, ‘consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear’. The morbid symptoms that we see all around us now, and which for many echo those that emerge in the 1930s, may bear witness to this kind of interregnum, this peculiar gulf between an old culture that is dying, and a new one that cannot be born – between what Raymond Williams would call residual and emergent social forms. In this interregnum, we witness morbid symptoms; we also see, amidst the inarticulacy that such periods of historical disorientation occasion, what Gramsci calls ‘the necessity of creating a new culture’.

Utopian imagining has always arisen from this faultline between the passing away and the yet to come. Think of the great burst of utopian possibility in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by figures such as Edward Bellamy, William Morris, H. G. Wells and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, in which the transformations of twentieth-century modernity – speed, telephony, film – produced a disorientation which was also a new relation to the future. As thinkers from Theodor Adorno to Fredric Jameson have argued, utopian images do not seek to counteract the crisis from which they originate, or to compensate for the failures that they witness. As Adorno writes in a dialogue with his friend Ernst Bloch, the utopian thought cannot find itself graven in an image, and does not have a language or an imagery of its own. We ‘are not allowed’, Adorno writes, ‘to cast the picture of utopia’, because ‘we do not know what the correct thing would be’. ‘Utopia’, he writes, ‘is essentially in the determined negation, in the determined negation of that which merely is, and by concretizing itself as something false, it always points at the same time to what should be’.

Utopia is not optimism. It is not, Bloch writes, ‘hurray-patriotism’. It derives its energy and its possibility from the sense that the very inarticulacy that emerges at times of crisis is also the darkness from which new images are born, and from which Gramsci’s new culture might arise. To be contemporary, to be attuned to the crisis that makes us unhappy in our own way, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben writes, requires us to attune ourselves to this darkness. ‘The contemporary’, Agamben writes, is he or she ‘who firmly holds their gaze on their own time so as to perceive not its light but its darkness’. To think or speak of utopia now is not to draw on existing reserves of imaginative of political capital, but rather to cast ourselves into a future in which we have no co-ordinates by which to orient ourselves. As the omni-crisis which we are living through unfolds, it becomes an urgent task to think past the existing terms in which we have related to each other, and to invent new ones. It is to this task that ‘Utopia Now’ is dedicated. The season brings musicians, dramatists, film makers and writers together with theorists, philosophers and critics from across the Arts, Humanities and Sciences, to ask what utopia means for us now, and to call for a collective utopian mode of critical thinking, now, in our time. The nature of the challenges that we face – technological, geopolitical, environmental – requires of us a refashioning of the terms in which we have conceived of modernity, Habermas’s unfinished project. The season ‘Utopia Now’ sets out to shape an environment in which some elements of that new thinking might become possible, so that we might see a way past the morbid symptoms of today, towards new social, political and aesthetic forms.

― Professor Peter Boxall

Peter Boxall is Goldsmiths’ Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford, and a Fellow of the British Academy. His books include Twenty-First-Century Fiction (2013), The Value of the Novel (2015), and The Prosthetic Imagination (2020), and his edited collections include 1001 Books (2006),and the Cambridge Companion to British Fiction: 1980-2018 (2019). He has been editor of Textual Practice since 2009. His volume of collected essays, The Possibility of Literature, came out in 2024, and he is currently at work on a book on Zadie Smith, entitled Life in Fiction.