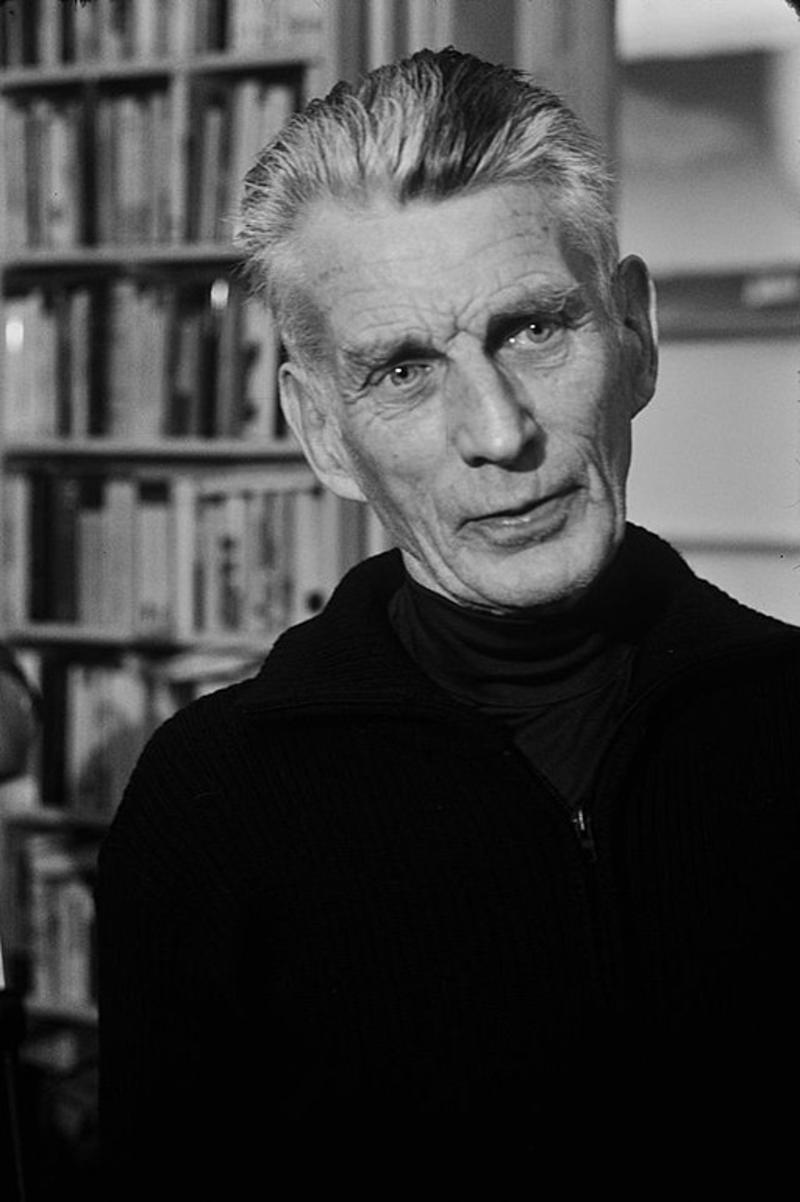

Spotlight on Research: Editing Beckett

Samuel Beckett’s manuscripts are scattered over more than a dozen archives on both sides of the Atlantic, which means that their study requires costly and sometimes complicated travel. That is why we try to reunite them digitally in the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project (BDMP), for which we recently received a 3-year research grant from the AHRC. The BDMP is a digital edition that gives access to all the manuscripts, with transcriptions, and enables you to follow the development of Beckett’s works.

If you are not sure how such an edition works, imagine a friendly, enthusiastic archivist. Let’s call her Winnie. She’ll be our guide and walk us through the edition.

Welcome to the BDMP. Mind your language going in. The edition is bilingual because Beckett wrote in two languages, French and English. It is also ‘genetic’ because it enables you to reconstruct the genesis of his writings. To develop this genetic bilingual edition, the project started from a digital archive of as much manuscript material as can be traced. We first made agreements with a dozen holding libraries across the world. Thanks to these agreements, we have already been able to compile a substantial digital archive of high-resolution images (c. 3285 scans), of which c. 30% (c. 1100 pages) still need to be transcribed. In concrete terms, this is the material that needs to be processed. During the next three years, we’ll focus on Murphy (written in the 1930s); the short prose (1920s-1980s); Play, Film (1960s); the TV plays (1960s-1980s); and Mal vu mal dit (1980s).

Feel free to have a look online at www.beckettarchive.org, especially the ‘free zone’, which contains a demo of Krapp’s Last Tape and of the Beckett Digital Library (BDL), alongside extensive documentation and several ‘sneak peeks’ into the material through notebook thumbnails, as well as some basic statistics on Beckett’s writing process across versions and works. Most recently, we added the first instalment of Breon Mitchell’s Samuel Beckett: A Bibliography: Part I: The Early Years: 1929–1950.

The BDMP currently has 10 modules, featuring the following works: Stirrings Still / Soubresauts and Comment dire / what is the word (2011), L’Innommable / The Unnamable (2014), Krapp’s Last Tape / La Dernière Bande (2015), Molloy (2017), Malone meurt / Malone Dies (2017), En attendant Godot / Waiting for Godot (2017), Fin de partie / Endgame (2018), Play / Comédie and Film (2019), Company / Compagnie (2021), Not I / Pas moi, That Time / Cette fois and Footfalls / Pas (2022). For each edition currently in the BDMP, the point of entry is a catalogue of all relevant documents that together constitute the work’s ‘genetic dossier’, in a chronological order. The Fin de partie / Endgame module, for instance, brings together material from five different partner institutions: The University of Reading, Trinity College Dublin, The Harry Ransom Center, Ohio State University and Harvard University.

Each document can be browsed in several ways. Another ‘About’ section offers a thumbnail of every page and metadata (such as a revision history and who is responsible for the transcriptions), while linking to the different ‘views’ the BDMP offers: the text view, the image view, the image/text view, and the TEI/XML view. The first presents the transcription as a running text. In the case of notebooks, the verso and recto pages are presented side by side. The transcriptions are useful if you just want to read the text of a document without having to brave Beckett’s sometimes near-illegible handwriting.

One advantage of the digital technology is its suitability for making connections between documents and versions. For the latter, the BDMP offers the possibility to compare versions sentence by sentence, which have all been numbered individually to this end: by selecting the option ‘compare sentences’ in either the image/text or text view, you get all the versions of a given sentence listed chronologically in the ‘synoptic sentence view’. The original language of composition appears first, followed by the language of the self-translation. Loose jottings (‘paralipomena’) that relate to the sentence but are not versions in the strictest sense, are also included.

Another option is to compare sentences using the CollateX automatic collation software that the BDMP has incorporated in its architecture. It highlights identical strings of words in green and variants in grey, based on the versions you want to collate. Similarly, the search function enables you to look for a word or a string of words across the BDMP. This is a particularly handy tool to explore Beckett’s use of intertextuality, made easier by means of a suggested search menu that includes ‘intertextual references’.

Another suggested search is for doodles, the presence and number of which usually indicate a point in the genesis when Beckett finds it hard to go on writing but wants to stay on the page nonetheless by means of drawing often elaborate shapes and symbols, classified in different categories.

Apart from all the available draft versions, the search for intertextual references also takes you to the Beckett Digital Library (BDL), which reconstructs the author’s personal library based on the volumes preserved at his apartment in Paris, further supplemented with archives and private collections. Continuously expanding as new material is discovered, it currently houses 762 extant volumes, as well as 247 virtual entries for which no physical copy has been preserved, but which letters or notebooks suggest he must have perused at some point.

And if you have any suggestions – for instance, if you think a word should be transcribed differently – there is a ‘your comments’ button which enables you to contact the editorial team directly, and if the Beckett experts agree, your suggestion will be incorporated and your contribution acknowledged and credited in the edition. All your feedback is very welcome.

—Professor Dirk Van Hulle