Spotlight on research: Write Cut Rewrite

Write Cut Rewrite exhibition. Photo by Ian Wallman

Before a book can be read, it needs to be written first. And writing almost always involves cutting and rewriting. As one of the most successful fiction authors ever, Stephen King gives the following advice: ‘kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings’. The phrase ‘kill your darlings’ is often attributed to the American modernist author William Faulkner, but he borrowed it from the British author Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (1863–1944). On Wednesday, 28 January 1914, Quiller-Couch, or ‘Q’, delivered a lecture at the University of Cambridge entitled ‘On Style’ – as part of a lecture series ‘On the Art of Writing’ – and he gave the audience this ‘practical rule’: ‘Whenever ... you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it – obey it whole-heartedly – and tear it up before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.’

Obviously, the metaphor of ‘killing’ or ‘murdering’ is chosen for dramatic effect. Usually, cutting, cancelling or otherwise undoing what you have written is so common that we hardly notice it. But in literature that means numerous passages have been undone by writers and never made it to publication. These cuts are the focal point of the exhibition ‘Write Cut Rewrite’, that runs at the Bodleian (Weston Library) until 5 January 2025, and of the book that comes with it: Write Cut Rewrite: The Cutting-Room Floor of Modern Literature (Oxford: Bodleian Library Publishing, 2024).

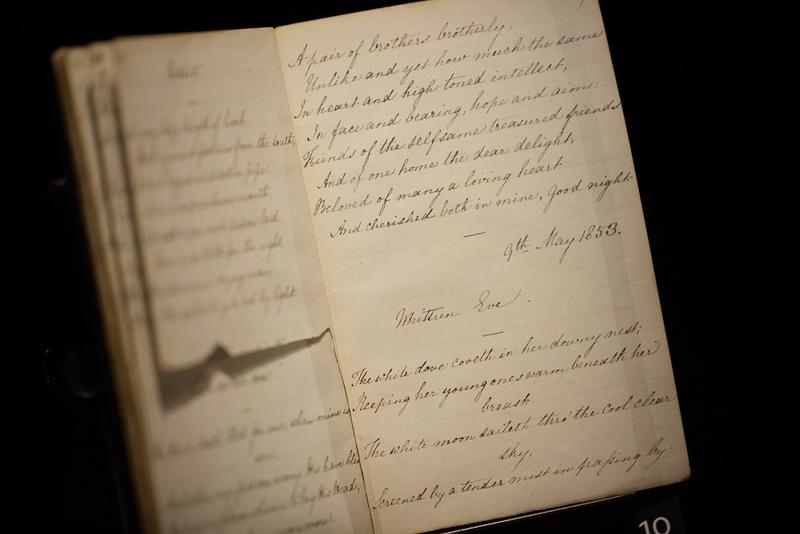

Christina Rosetti's poem 'Portraits' shows a torn page where the second stanza has been removed. Photo by Ian Wallman

The emphasis is on modern manuscripts, but the phenomenon of killing your darlings is much older. For example, the Ormulum is a 12th-century notebook containing almost 19,000 lines of verse by Orm, commenting on the Bible in early English. The document consists of pieces of parchment of the lowest quality: sometimes just the outer part of hides. For a notebook that is almost a thousand years old it looks surprisingly modern because it features so many crossed-out passages. It shows someone in mid-thought, using a quill and parchment to give shape to their ideas.

So, the Ormulum at the Bodleian shows that there are Medieval autograph manuscripts – it has actually been identified as the earliest surviving autograph manuscript in English. But this example is so rare that it can be seen as an exception confirming the rule that the majority of early manuscripts in English that are still extant are by scribes, not by the authors themselves. Most of the examples in the exhibition are therefore no older than the eighteenth century.

Alexander Pope, for instance, prepared a manuscript of An Essay on Criticism which contains many famous lines, such as ‘To err is human; to forgive, divine’ and ‘Fools rush in where angels fear to tread’. The manuscript also features several deletions, such as the passage on pedantic teachers: ‘Many are spoil’d by that Pedantic Throng / Who, with great Pains, teach Youth to reason wrong’. These lines are part of an eight-line passage that was crossed out by Pope before the Essay was first published in 1711. The manuscript of more than 800 lines was reduced to less than 750.

The exhibition features abandoned works, such as Jane Austen’s The Watsons, and cases of censorship, such as Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. It also touches on the revisions and rewritings of famous books, offering visitors a unique chance to look over the shoulder of literary greats at the moment of creation. Highlights include discarded ideas, fundamental changes, deletions, additions, notes and scribbles from authors such as Jane Austen, Christina Rossetti, James Joyce, Raymond Chandler, Ian Fleming, and John le Carré. Other insights from the cutting-room floor include the original ending to Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, the sketches in Alice Oswald’s notebooks, George Eliot’s reading notes, Franz Kafka’s cuts in the manuscript of his novel The Castle and a description in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, extracted from Percy Shelley’s journal. And in the digital age, the traces of the writing process are not necessarily lost, but sometimes become part of the poetry as in the keystroke-logged poem ‘Cuttings’ by Franny Choi, published by the online journal Midst under the motto: ‘What if you could watch your favorite poet write?’

Photo by Ian Wallman

Cutting is a form of creative undoing that involves more than just authors cancelling words in their drafts. Writers are also readers; they take notes, some of which are processed in their own work, but many of which remain vestigial. Like vestigial limbs or vestigial organs, they have no direct function in the finished product, but they did have a function in the creative production process. The writer decided not to include them in their work.

One would expect these ‘cuts’ to disappear in the waste-paper basket. But very often, writers do not throw them away. Many writers even donate their manuscripts to libraries and archives, like the Bodleian, where they are carefully preserved. They testify to the hard work that goes into the writing process. The exhibition takes visitors into authors’ workshops. It draws on the richness of the Bodleian Library’s collection of modern manuscripts and combines these treasures with manuscripts by Samuel Beckett from the University of Reading’s Special Collections and the British Library.

― Professor Dirk Van Hulle

Dirk Van Hulle is Professor of Bibliography and Modern Book History at the University of Oxford, director of the Oxford Centre for Textual Editing and Theory (OCTET), and author of Genetic Criticism: Tracing Creativity in Literature (OUP, 2022).

The Write Cut Rewrite exhibition runs at the Bodleian (Weston Library) until 5 January 2025. The accompanying book, Write Cut Rewrite: The Cutting Room Floor of Modern Literature, is available to buy via the Bodleian Library website.