‘The Knight’s Tale’ by Geoffrey Chaucer and ‘Emily’ by Patience Agbabi

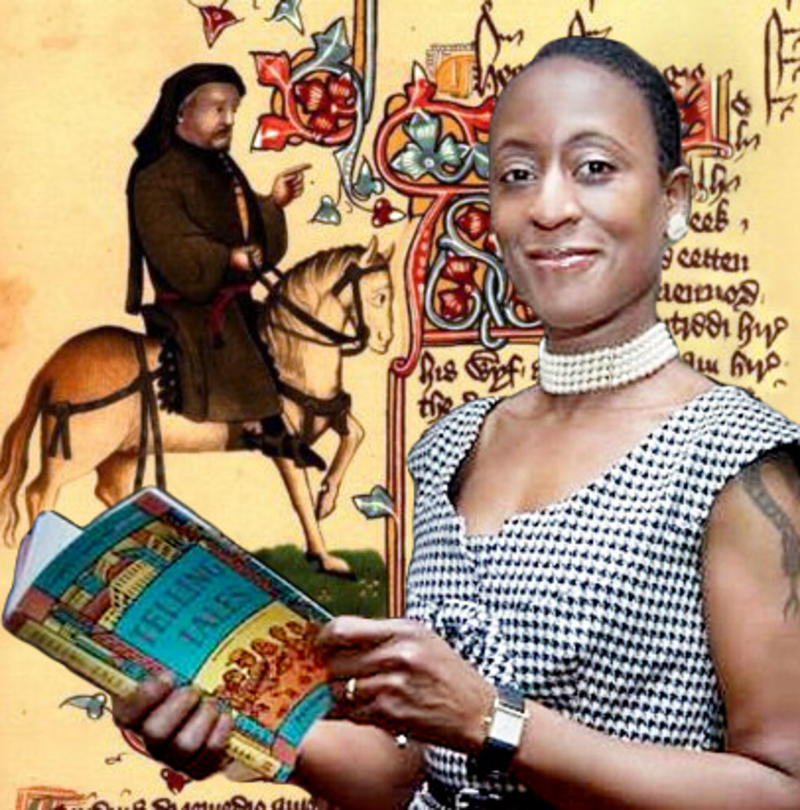

Geoffrey Chaucer as a pilgrim, and Patience Agbabi with Telling Tales.

Image of Chaucer as a pilgrim from Ellesmere Manuscript in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California (Public domain); Patience Agbabi (CC BY-SA 4.0) via Wikimedia Commons

Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1342–1400) is best known for the Canterbury Tales, a tale-collection in which a motley crew of pilgrims competes to see who can tell the best tale on their way from Southwark in London to the Thomas Becket shrine in Canterbury. One of the most striking aspects of the text is Chaucer’s insistence that we should listen to tales told by people from different backgrounds and levels of society. The ‘Knight’s Tale’ is a tale of courtly love and male competition, but many readers think it implicitly critiques some of the values of chivalry. These values are then openly mocked in the tale that follows, the ‘Miller’s Tale.’ Here, an excerpt from the ‘Knight’s Tale’ is paired with a modern re-telling of the tale by Patience Agbabi, a Nigerian-British poet, whose Telling Tales adapts the Canterbury Tales for modern times.

In the ‘Knight’s Tale,’ Palamon and Arcita are confronting two different forms of constraint. They have been captured by Theseus, and are confined by him in a prison. There, they see and fall madly in love with Emily and lose control over their own feelings and minds. The two kinds of imprisonment both take away their freedom and force them to live and act in ways that they cannot control. I find it really interesting to think about Chaucer’s own experience of imprisonment in connection with this tale: he was a prisoner of war in France when he was a teenager, and was ransomed by Edward III for £16, equivalent to somewhere between £10,000 and £25,000 now.

The link between physical imprisonment and mental imprisonment is brought out in Patience Agbabi’s poem, ‘Emily.’ She explicitly links the prison cell and the brain cell throughout her poem, blurring the boundaries between what is happening to the men in an external reality, and what is happening inside their heads. Agbabi develops the medieval idea of love as a prison and the lover as abject and unfree using the modern language of psychology (ego and id).

In the ‘Knight’s Tale, as Palamon roams in his room, Emily roams in the enclosed garden. She too is a prisoner of war, taken by Theseus. Later in the tale, Emily says that she wants to ‘walk in the woods wild,’ as befits an Amazon (a female warrior) but she is instead forced into marriage by Theseus. Agbabi also depicts Emily as the object of male desire, wanted by all, treated as a trophy to be fought for – but she blurs the boundaries of identity itself with her provocative conclusion ‘I’m Emily.’

Agbabi takes Chaucer as an inspiration, but does something new – as we can also see in other adaptations of Chaucer, including Pier Paulo Pasolini’s film, The Canterbury Tales (1972), the BBC TV adaptations, Canterbury Tales (2003), or Marilyn Nelson’s Cachoeira Tales (2019). Chaucer himself used many sources creatively. The ‘Knight’s Tale’ is based on the Teseida by the Italian poet Boccaccio and is also influenced by other texts including Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy. Both Chaucer’s writing and Agbabi’s emerge from multiple cultures, languages, and histories. These poets pay conscious homage to what came before, while also blazing new trails.

—Marion Turner

Some themes and questions to consider

- Why are so many modern poets, filmmakers, and other artists inspired by Chaucer?

- In what ways is Emily depicted as a blank space for male desire?

- What do the poems suggest about the true nature of freedom?

- Do you think these poems are more concerned with male competition or with sexual desire?

- How did the form of these two poems – the rhymes, patterns and rhythms these poets chose – change the way you read the story they tell?

“The Knight’s Tale” by Geoffrey Chaucer

This story is told by a Knight to a group of fellow pilgrims. Before these excerpted lines, Duke Theseus, after conquering Hippolyta’s kingdom, and then marrying Hippolyta, has made war to regain the city of Thebes from its governor, Creon, and won. After the battle, Theseus takes two knights as prisoners of war: Palamon and Arcita (who are cousins). It is whilst living out their long imprisonment together, that these two first see Emily. The power of this encounter destroys their friendship and propels them both on a journey towards mortal conflict.

The Knight’s Tale

(lines 204–318)

Bright was the sun and clear that morning,

And Palamon, this woeful prisoner,

As was his custom, by permission of his jailer,

Had risen and roamed in a chamber on high,

In which he saw all the noble city,

And also the garden, full of green branches,

Where this fresh Emily the shining

Was walking, and roamed up and down.

This sorrowful prisoner, this Palamon,

Goes in his chamber roaming to and fro

And to himself complaining of his curse

That he had been born, saying often, “alas!”

And so it happened, by chance or accident,

That through a window, thick with many a bar

Of iron, great and square as any beam,

He cast his eye upon Emily,

And with that he blanched and cried, “A!”

As though he were stung unto the heart.

And with that cry Arcita immediately started

And said, “Cousin mine, what ails you,

Who are so pale and deadly to look at?

Why did you cry out? Who has done you offence?

For God’s love, take patiently

Our imprisonment, for it may no otherwise be.

Fortune has given us this adversity.

Some wicked aspect or disposition

Of Saturn, by some constellation,

Has given us this, although we had sworn it would not be;

So stood the heavens when we were born.

We must endure it; this is the short and plain.

This Palamon answered and said again:

“Cousin, truly, in this opinion

You have a vain imagination.

This prison did not cause me to cry out,

But I was hurt right now through my eye

Into my heart, that will be my bane.

The fairness of that lady whom I see

Yonder in the garden roaming to and fro

Is the cause of all my crying and my woe.

I know not whether she is woman or goddess,

But truly it is Venus, as I guess.”

And with that he fell down on his knees,

And said, “Venus, if it be thy will

Thus to transfigure yourself in this garden

Before me, sorrowful, wretched creature,

Help that we may escape out of this prison.

And if it be so that my destiny is shaped

By eternal decree to die in prison,

Have some compassion on our lineage

Which is brought so low by tyranny.”

And with that word Arcite goes to see

Where this lady roamed to and fro,

And with that sight her beauty hurt him so,

That, if that Palamon was wounded sore,

Arcite is hurt as much as he, or more.

And with a sigh he said piteously,

“The fresh beauty slays me suddenly

Of her who roams in the yonder place;

And unless I have her mercy and her grace,

So that I can at least see her,

I am as good as dead; there is no more to say.”

This Palamon, when he those words heard,

Dispitiously looked and answered,

“Do you say this in earnest or in play?”

“Nay,” said Arcita, “in earnest, by my faith!

So help me God, to play pleases me evilly.”

This Palamon began to knit his brows.

“It would not be,” said he, “any great honour to you

To be false, nor to be traitor

To me, that is your cousin and your brother

Sworn deeply, and each of us to the other,

That never, on pain of death,

Until death shall dispatch us two,

Neither of us shall hinder the other in love,

Nor in anything else, my dear brother,

But rather you should further me

In every case, as I shall further you —

This was your oath, and mine also, certainly;

I know very well, you dare not deny it.

Thus are you my closest counsel, without doubt,

And now you would falsely prepare

To love my lady, whom I love and serve,

And ever shall until my heart dies.

Nay, certainly, false Arcita, you shall not so.

I loved her first, and told you my woe

As my confidant and my sworn brother

To help me, as I have told before.

For which you are bound as a knight

To help me, if it lies in your power,

Or else you are false, I dare well say.”

This Arcita proudly spoke back:

“You shall,” said he, “be rather false than I;

And you are false, I tell you plainly.

As a lover, I loved her first before you.

What can you say? You do not know

Whether she is a woman or goddess!

Yours is a feeling of holiness,

And mine is love as to a creature;

For which I told you my circumstance

As my cousin and my sworn brother.

I posit: that you loved her first;

Do you not know the old saying?

That ‘who shall give a lover any law?’

Love is a greater law, by my skull,

Than may be given to any earthly man;

And therefore manmade law and such decree

Is broken every day for love in every degree.

A man must necessarily love, in spite of his head;

He can not flee it, even if it kills him,

Whether she is a maid, or widow, or wife.

And also it is not likely in all your life

To stand in her grace; no more shall I;

For well you know yourself, truly,

That you and I are condemned to prison

Perpetually; no ransom can help us.

“Emily” by Patience Agbabi

In this poem, which translates and transforms Chaucer’s “The Knight’s Tale”, two brothers-at-arms, imprisoned together by war and then torn apart by love of the same woman, are reimagined with new voices and a story that is both different and the same.

Emily

In Chaucer’s story there are two heroes, who are practically indistinguishable from each other, and a heroine, who is merely a name.

J R Hulbert

Arc? Dead. And if you’re sniffing for his body

you won’t find nothing: ransack the Big Smoke

from Bow to Bank. Arc fell for Emily

ten feet deep . . . I’m Pal, Emily’s alter.

Think ego. Arc and me, we shared a cell

for months, it was a shrine to her, a temple.

I miss him, like a gun to the temple.

Too close. Two men locked in a woman’s body,

her messed-up head. When I say shared a cell

I’m talking brain. She became us. Arc smoked

the Romeos, and me, I smoked all tars,

we breathed out on her name ah! Emily.

Blonde, with blacked out highlights, Emily.

Our host, the goddess. Looks are temporal.

Who reads her diagnosis? It don’t alter

the facts. She made me up to guard her body

from predators, the silhouettes in smoke.

It’s when she wears the hour glass and plays damsel,

she lets me out. It messes with their brain cells,

my voice, her face. All men want Emily,

they think they have a right. It don’t mean smoke.

She acts like growing up was Shirley Temple

and don’t remember nothing, but her body

knows what happened happened on that altar.

Think bed . . . Arc’s dead. Broke his parole, an alter

crazy on id, he starved us all to cancel

me out for good. It’s written off, our body.

He fought to win: I fought for Emily.

I’m dead beat, but I won up here, the temple,

the messed-up head. Sent her a ring of smoke.

Having a big fat Romeo to smoke

don’t make you Winston Churchill. Arc was altered.

He won the war but lost the plot. The temple

became his tomb. And me, I got the damsel.

She don’t know yet. We’re stitched up, Emily,

one and the same, one rough cut mind, one body . . .

Must’ve blacked out . . . This body ain’t no temple

but what’s the alternative, a padded cell?

Got anything to smoke? . . . I’m Emily . . .

© 2011, Patience Agbabi

From: Poetry Wales, Winter 48.3, 2012/13

Find out more about Patience Agbabi

Profile on Agbabi at Writers Make Worlds

Patience Agbabi in conversation with Elleke Boehmer and Marion Turner about Telling Tales and her contribution to the 2016 Refugee Tales project

Buy Patience Agbabi’s Telling Tales at Blackwell’s

Find out more about Geoffrey Chaucer

Profile on Chaucer at Great Writers Inspire

Read Harvard Translations of the Canterbury Tales

Read non-anglophone adaptations from the Global Chaucers Archive

About the Contributor

Marion Turner is a Tutorial Fellow and Associate Professor of English at Jesus College, University of Oxford. She has published widely on Chaucer and late-medieval literature, including Chaucerian Conflict (OUP, 2007) and A Handbook of Middle English Studies (Wiley Blackwell, 2013). Her biography of the poet, Chaucer: A European Life (Princeton, 2019) recently won the British Academy Rose Mary Crawshay Prize 2020, was shortlisted for the Wolfson History Prize 2020, and was named as a Book of the Year 2019 by the Times, the Sunday Times, and the TLS. It will be out in paperback in September 2020. You can watch her in conversation with the novelist Matthew Kneale here or hear her talk about Chaucer on Radio 4’s Start the Week here.