The Exeter Book riddles

‘Who am I?’

This question lurks in all stories, poems, speeches that use the first person, the ‘I’ voice: from a Shakespeare soliloquy, to a Victorian novel, to a contemporary poem. One of the texts below directly asks ‘Say what I’m called’, but all probe these questions of identity, and of how we relate to the voices and things around us.

What are these texts? They’re riddles in Old English. In some an object speaks about itself (a technique known by the Greek word prosopopoeia), while others are told by an observer, marvelling at the strangeness of the thing they’re describing. These riddles invite us to search for meaning, play with words, and take pleasure in an eventual recognition. Sometimes the solution is obvious, sometimes ridiculous, but along the way they investigate the natural world and its transformations; a whole spectrum of emotions; gender and hierarchy; the power of language; death and what comes after; and the lives of objects – not to mention jokes about sex.

This selection is from the Exeter Book, a manuscript written late in the tenth century CE. It was bequeathed to the monastery at Exeter in Devon by a bishop called Leofric in 1072, and is still in the cathedral library there. In Leofric’s will, it’s described as ‘one big English book about various things, composed in poetry’. It’s one of the great treasures of English literature, containing many beautiful and haunting poems which demonstrate the rich culture of Anglo-Saxon (pre-Conquest) England. It includes about a hundred riddles, some being versions of Latin riddles (aenigmata).

The Exeter Book’s texts look at first like prose, written right across the page in a stylish, clear script. But when read aloud, they reveal that they are composed in Old English verse, which uses alliteration to structure its lines, along with a four-stress beat based on the important words in each line. Those lines usually have two or three stresses that alliterate, and one (the last one) that doesn’t, with a gap (caesura) in the middle. An equivalent in modern English would be this line:

I browse an old book, to banish my sorrow.

Here, ‘browse’, ‘book’, ‘banish’ and ‘sorrow’ carry the main stress. The first three alliterate, and the caesura after ‘book’ gives balance to the line, placing one action (reading) in apposition to its effect (banishing sorrow). This balance, rhythm and movement are integral to the sound qualities of Old English verse, which is designed to be heard, even when it’s written down.

—Nicholas Perkins

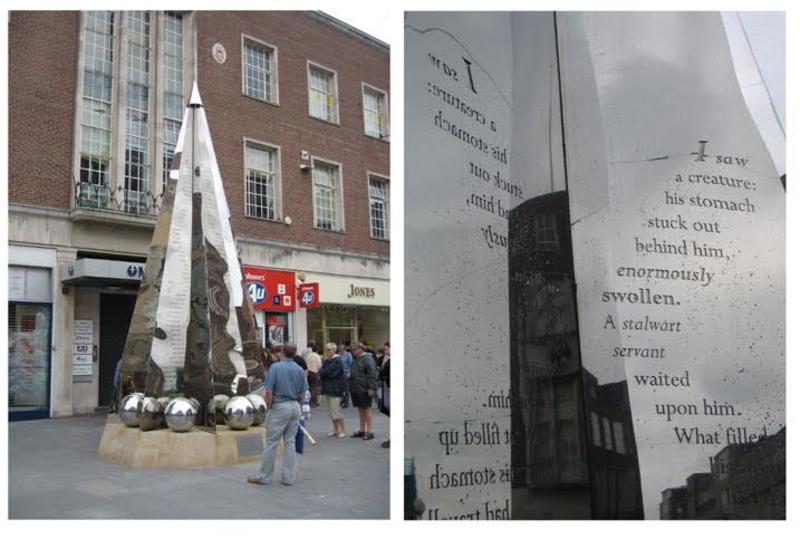

The Exeter Riddle sculpture was designed by artist Michael Fairfax and installed in Exeter city centre in 2005. Modern English versions of some of the Old English riddles are incised in mirror writing on its wings, and can be read in their reflection, with solutions on the orbs below. The whole thing becomes a hall of mirrors, reflecting, doubling and distorting.

[Photograph: Michael Fairfax]

Audio

Nicholas Perkins spoke to Dr Harriet Soper (Lincoln College, Oxford) about these riddles. Listen to their conversation:

Clip 1: Introduction to the Exeter Book riddles

Clip 2: The function of riddles

Clip 3: Ideas about nature in the early Middle Ages

Clip 4: Prosopopoeia in the riddles

Clip 5: Suggestions for exploring more of the Riddles

The Exeter Book

If you’d like to know the answers to the riddles, scroll to the end, but see if you can guess first!

5

Ic eom anhaga, iserne wund,

bille gebennad, beadoweorca sæd,

ecgum werig. Oft ic wig seo,

frecne feohtan. Frofre ne wene,

þæt me geoc cyme guðgewinnes,

ær ic mid ældum eal forwurðe,

ac mec hnossiað homera lafe,

heardecg heoroscearp, hondweorc smiþa.

Bitað in burgum; ic abidan sceal

laþran gemotes. Næfre læcecynn

on folcstede findan meahte,

þara þe mid wyrtum wunde gehælde,

ac me ecga dolg eacen weorðað

þurh deaðslege dagum ond nihtum.

I live alone, wounded by iron,

Slashed by a sword, exhausted by war work,

Worn out by weapons. I often see battle,

Fierce conflicts. I don’t count on

Getting relief from fighting

Before I’m totally destroyed among people;

Instead, I’m battered by hammer-worked blades,

Hard edged, dagger sharp, the handiwork of smiths.

They cut me in the citadel; I must wait for

A worse encounter. I can never

Find doctors in the dwelling place

Who could heal my wounds with herbs,

But my blade cuts grow bigger

Through deadly blows, day and night.

45

Ic on wincle gefrægn weaxan nathwæt,

þindan ond þunian, þecene hebban.

On þæt banlease bryd grapode,

hygewlonc hondum. Hrægle þeahte

þrindende þing þeodnes dohtor.

Swelling, poking, tenting its cover.

A girl gripped what was boneless,

A cocky woman with her hands. She covered under a hood

That bulging thing, did the lord’s daughter.

47

wrætlicu wyrd, þa ic þæt wundor gefrægn,

þæt se wyrm forswealg wera gied sumes,

þeof in þystro, þrymfæstne cwide

ond þæs strangan staþol. Stælgiest ne wæs

wihte þy gleawra, þe he þam wordum swealg.

A strange event, when I heard about that wonder –

That a worm gobbled up some man’s song,

A thief in the dark downed a glorious speech

And its firm foundation. The stealing guest

Was none the wiser, for all the words he’d swallowed.

51

samed siþian; swearte wæran lastas,

swaþu swiþe blacu. Swift wæs on fore,

fuglum framra fleag on lyfte;

deaf under yþe. Dreag unstille

winnende wiga, se him wegas tæcneþ

ofer fæted gold feower eallum.

Travelling as one. The tracks were dark,

Bible-black footmarks. It was quick to move,

Flew through the air faster than bird flocks,

Dived under waves. He worked hard,

That striving soldier, who pointed the paths

Over burnished gold to all four.

68/69

heo wæs wrætlice wundrum gegierwed.

Wundor wearð on wege; wæter wearð to bane.

It was amazingly adorned with marvels.

A wonder happened on the wave: Water become bone.

85

ymb <* * *> unc dryhten scop

siþ ætsomne. Ic eom swiftre þonne he,

þragum strengra, he þreohtigra.

Hwilum ic me reste; he sceal yrnan forð.

Ic him in wunige a þenden ic lifge;

gif wit unc gedælað, me bið deað witod.

My house isn’t quiet, but I’m not loud

About [***] the lord made for us two

A path together. I’m quicker than he is,

Sometimes more strong; he labours longer.

At times I rest, but he must keep going.

I always live in him for as long as I last;

If we two divide, my death’s undoubted.

* missing text in the manuscript

86

monige on mæðle, mode snottre.

Hæfde an eage ond earan twa,

ond II fet, XII hund heafda,

hrycg ond wombe ond honda twa,

earmas ond eaxle, anne sweoran

ond sidan twa. Saga hwæt ic hatte.

Many were meeting, wise in their mind.

It had an eye and two ears,

Two feet, twelve hundred heads,

A back and belly, and two hands,

Arms and shoulders, also one neck

And two sides. Say what I’m called.

Texts and translations prepared by Nicholas Perkins. The Old English text includes some old letter forms: æ (called ash), pronounced ‘a’ as in ‘apple’; þ (thorn) and ð (eth), used for ‘th’, either the unvoiced sound as in ‘therapy’, or the voiced sound as in ‘their’.

Solutions

5: a shield (described as a wounded warrior; but also like a chopping board)

45: dough that’s rising (but also playing with (the sense of) an erect penis)

47: a book moth larva nibbling a manuscript (also thinking about what it means to read)

51: three fingers holding a quill pen, writing a manuscript

68/69: probably an iceberg

85: the soul, living in a body; or, a fish in a river

86: a one-eyed garlic seller (yes, really!)

Some themes and questions to consider

- Do the speaking objects in these riddles (especially numbers 5 and 85) or the narrating voices have stable identities, and how do you relate to those identities as a reader or listener?

- Look out for the way that Old English poetry layers its descriptions, using a technique known as repetition and variation to build up a patchwork of images and references. How does that affect your response?

- Is there an ethical or moral content to these riddles? What do you think is gained or lost from imagining objects as having a conscious life, or an ethical awareness?

- If you could write a riddle a bit like these, based on a contemporary object, what would you chose? How about trying it out and seeing what you come up with?

Learn More

The Riddle Ages

Website run by Dr Megan Cavell, that includes texts, translations and commentary on all the Exeter Book riddles, as well as other riddle collections from the Middle Ages.

Megan Cavell, ‘The Exeter Book Riddles in Context’

Blog on the British Library website.

Digitized images of the Exeter Book

The riddles we’ve included in this post are on folios 102 verso; 112v; 112v – 113 recto; 113r–v; 125v; 128v; 128v – 129r.

Rachel A. Burns, ‘Riddling with Things’

Ideas for teaching and discussing Exeter Book Riddles, with links to texts and pictures of Anglo-Saxon objects.

Cambridge University Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, ‘The Spoken Word’

Introduction to and audio extracts from the different languages spoken in Britain and Ireland in the early Middle Ages.

About the Contributors

Nicholas Perkins is Associate Professor of English at St Hugh’s College, University of Oxford. He was brought up in Essex, and studied at Cambridge University before coming to Oxford to teach and research medieval literature. He has written or edited a number of books, including The Gift of Narrative in Medieval England (2021), Medieval Romance and Material Culture (2015), and Anglo-Saxon Culture and the Modern Imagination (2010, ed. with David Clark). In 2012 he curated a major exhibition in the Bodleian Library, The Romance of the Middle Ages, and in 2023 he is curating another, called Gifts and Books, along with an accompanying book of essays.

In the audio link, Nick is in conversation with Dr Harriet Soper, Fellow in English at Lincoln College. Harriet teaches and writes on various aspects of medieval literature, but she has a particular interest in depictions of ageing in Old English poetry (including in the Exeter Book riddles); her first book, The Life Course in Old English Poetry, is due to be published later this year.