‘The Slave Auction’ and ‘Bury Me in a Free Land’ by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

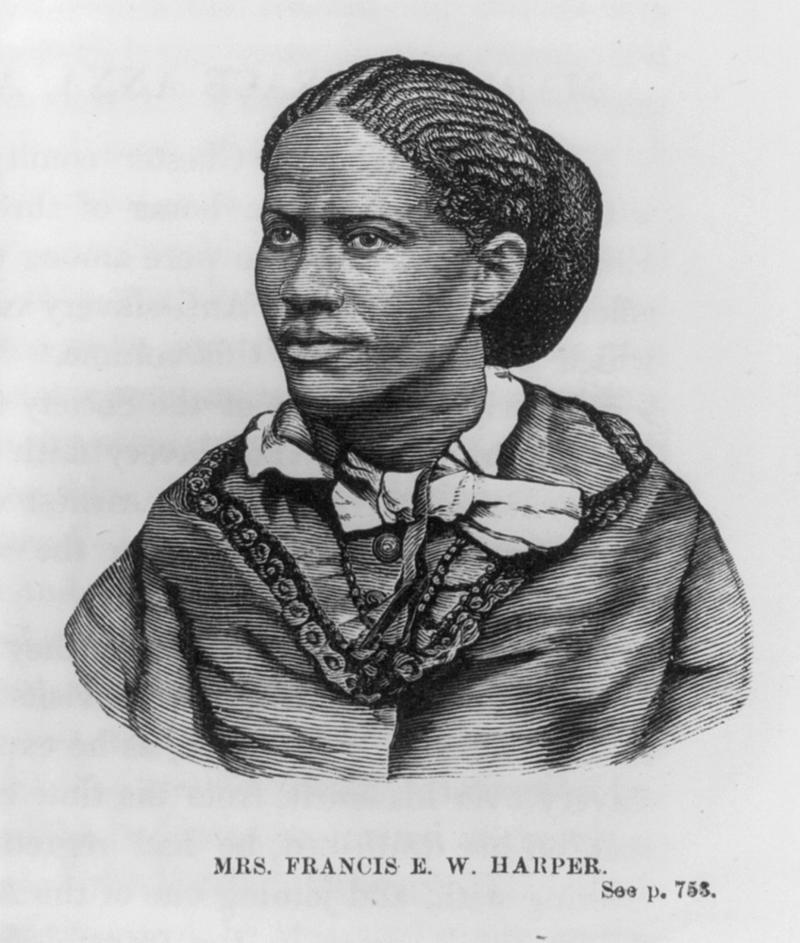

Francis Ellen Watkins Harper

Originally published in William Still, The Underground Railroad (1872), p. 748.

[Public Domain via the US Library of Congress]

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s poems are some of the most influential of the mid-nineteenth century United States. Their impact continues to today, inspiring generations of poets and authors.

Her nuanced representations of slavery – including the enslavement of women – are vital testaments to the racism, injustice and violence in America immediately prior to the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, while revealing the power of the cultural resistance enacted by Harper and her peers. Later in her life, Harper began embracing other literary genres, as can be seen in her novel Iola Leroy (1892), one of the first novels published by an African American woman writer.

Born a free woman in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1825, Harper started her career as a teacher and a volunteer for the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. After joining the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1853, she publicly campaigned against the enslavement of African Americans by composing anti-slavery poetry, using it as a crucial tool in her fight for abolitionism.

Harper published Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects in 1854, which included ‘The Slave Auction’, ‘Eliza Harris’, and ‘The Slave Mother’. Several years later, she composed ‘Bury Me in a Free Land’ (published in The Anti-Slavery Bugle in 1858). Harper regularly performed her poetry at public abolitionist campaigns hosted by the American Anti-Slavery Society, before and after they were published in print. Her compelling skills as an orator are reflected in the style of language chosen for written publication. Her bold, visceral images and rhyming couplets (as seen in ‘The Slave Auction’ with line endings such as ‘eyes’, ‘sold’, ‘cries’, and ‘gold’) resulted in memorable verse which replayed in the minds of audience members listening to Harper recite her words – and these poetic devices became just as memorable for readers engaging with the printed versions which were reproduced in newspapers and periodicals across the US. This memorability ensured that those reading or listening to her verse were forced to confront the central themes of her writing – the horrors of slavery and the urgency of abolitionism – demonstrating the political power of poetry.

Many of her poems, especially those collected in Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, express the relationship between enslaved mothers and their children, including children who died prematurely. Based on true accounts Harper had heard and witnessed, she exposed the appalling violence experienced by enslaved women in the nineteenth century, drawing attention to the intersections between racism, misogyny, and patriarchy in American society.

In ‘Bury Me in a Free Land’, Harper’s speaker describes ‘the mother’s shriek of wild despair / Rise like a curse on the trembling air.’ Harper used emotive metaphors to give voice to the experiences of fellow African American women who were silenced and denied autonomy. As the poem concludes, the speaker emphatically declares that ‘All that my yearning spirit craves’ is a ‘land’ where slavery is abolished and its brutality has ended.

As Koritha Mitchell observes in From Slave Cabins to the White House (2020), ‘Harper’s [writing] contributes to the community conversation’ as she ‘asserted her right to belong in the nation’. Harper’s poetry is sophisticated, compelling and politically urgent, and her themes and questioning of identity continue to carry heart-wrenching weight well into the twenty-first century.

—Daniele Nunziata

‘The Slave Auction’ (1854)

The sale began—young girls were there,

Defenseless in their wretchedness,

Whose stifled sobs of deep despair

Revealed their anguish and distress.

And mothers stood, with streaming eyes,

And saw their dearest children sold;

Unheeded rose their bitter cries,

While tyrants bartered them for gold.

And woman, with her love and truth—

For these in sable forms may dwell—

Gazed on the husband of her youth,

With anguish none may paint or tell.

And men, whose sole crime was their hue,

The impress of their Maker’s hand,

And frail and shrinking children too,

Were gathered in that mournful band.

Ye who have laid your loved to rest,

And wept above their lifeless clay,

Know not the anguish of that breast,

Whose loved are rudely torn away.

Ye may not know how desolate

Are bosoms rudely forced to part,

And how a dull and heavy weight

Will press the life-drops from the heart.

‘Bury Me in a Free Land’ (1858)

You may make my grave wherever you will,

In a lowly vale or a lofty hill;

You may make it among earth’s humblest graves,

But not in a land where men are slaves.

I could not sleep if around my grave

I heard the steps of a trembling slave;

His shadow above my silent tomb

Would make it a place of fearful gloom.

I could not rest if I heard the tread

Of a coffle-gang to the shambles led,

And the mother’s shriek of wild despair

Rise like a curse on the trembling air.

I could not rest if I heard the lash

Drinking her blood at each fearful gash,

And I saw her babes torn from her breast

Like trembling doves from their parent nest.

I’d shudder and start, if I heard the bay

Of the bloodhounds seizing their human prey;

If I heard the captive plead in vain

As they tightened afresh his galling chain.

If I saw young girls, from their mothers’ arms

Bartered and sold for their youthful charms

My eye would flash with a mournful flame,

My death-paled cheek grow red with shame.

I would sleep, dear friends, where bloated might

Can rob no man of his dearest right;

My rest shall be calm in any grave,

Where none calls his brother a slave.

I ask no monument, proud and high

To arrest the gaze of the passers by;

All that my yearning spirit craves,

Is—bury me not in the land of slaves.—

Some themes and questions to consider

-

How do you respond to the intersections between enslavement and misogyny in Harper’s verse?

-

Why is it important to learn the identity of the speaker of a poem?

-

How important are religious themes here?

-

How do Harper’s poems reflect the spoken quality of performance? We recommend you try reading these poems aloud (either alone or as part of an audience)!

-

Who is permitted to narrate history? How does the telling of history relate to freedom?

Full text

The full text of Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects can be found for free at Project Gutenberg.

Connections

If you’re looking for a longer reading experience, you could bring this text alongside Mary Prince’s abolitionist life-writing from the early nineteenth century from Season 1. Prince experienced enslavement first-hand.

More on Francis Ellen Watkins Harper and her work

‘Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Fighting for the Rights of All’

YouTube biography of Harper’s life and work by Preservation Maryland.

Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E. W. Harper, 1825–1911

Melba Joyce Boyd, Wayne State University Press, 1995. [Google Preview]

Sowing and Reaping: A “New” Chapter from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s Second Novel.’

Article on Harper’s literary reputation, and the history of her second novel by Eric Gardner, Commonplace: The Journal of Early American Life, vol. 13, no. 1, October 2012.

‘Poetry towards Progress: Frances E. W. Harper’

Blog post by Erin Rushing for the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

More from Oxford Scholars

Great Writers Inspire: Poetic Miscellanies

Find out more about the culture of poetic miscellanies, or the popular publication of ‘Poems on Various Subjects’.

Writers Make Worlds: Identifying with Literature

Read more deeply about questions of identification and performance in poetry.

About the Contributor

Dr Daniele Nunziata is Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Oxford. He specialises in postcolonial and world literatures, and primarily teaches at St Anne’s College and the Oxford Prospects and Global Development Institute. His first book is Colonial and Postcolonial Cyprus: Transportal Literatures of Empire, Nationalism, and Sectarianism (2020). His research has been published widely in various peer-reviewed journals, including PMLA and the Journal of Postcolonial Writing, and he contributes to Great Writers Inspire and Writers Make Worlds. He received an ECR Research Grant Award from St Anne’s College, and has co-chaired conferences with Oxford Comparative Criticism and Translation and Meeting Minds Global. Nunziata’s poetry has been published in many international journals, including Poetry London, and has been broadcast live on BBC Radio.