The Tunnel by Dorothy Richardson

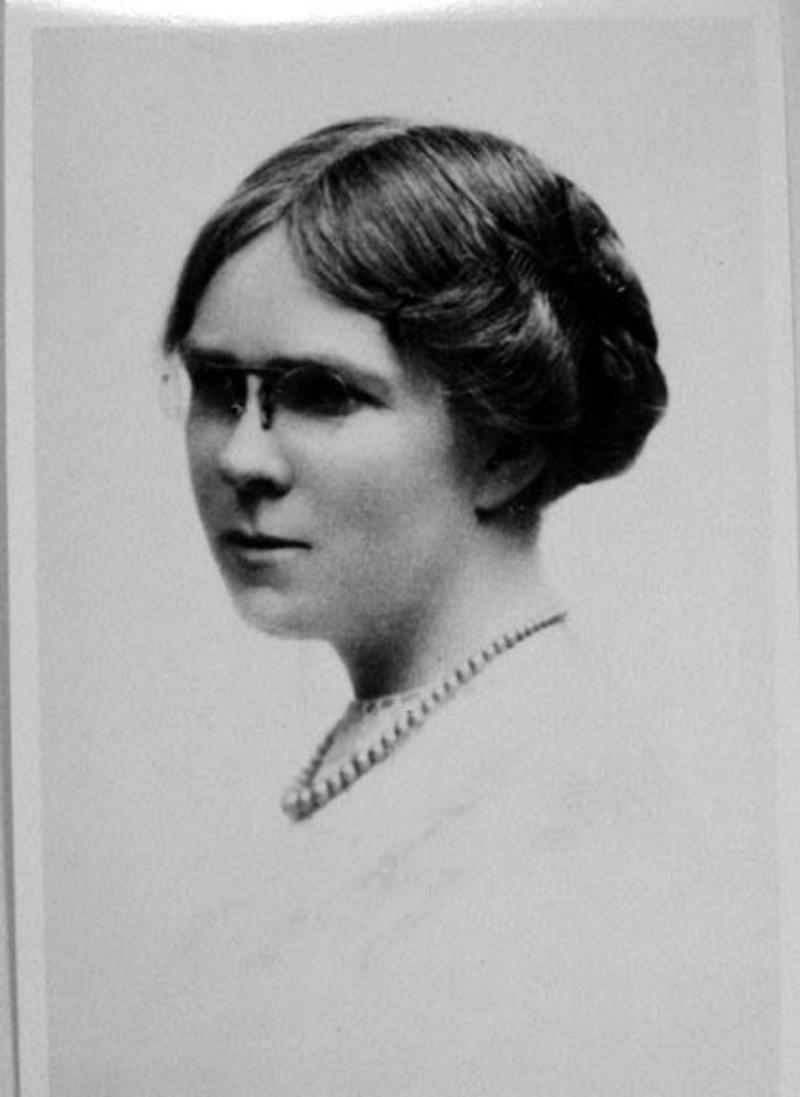

Dorothy Richardson

[Photographer unknown; all attempts were made to trace the copyright holder]

Dorothy Richardson is best-known for writing Pilgrimage, a sequence of thirteen novels that follows the life of a character called Miriam Henderson between the ages of about seventeen and forty. Miriam’s experience closely follows Richardson’s own, and for this reason Pilgrimage is often considered to be a fictionalized autobiography. With Pilgrimage, Richardson created a uniquely detailed and deeply personal record of the life of an educated British woman in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

The Ten-Minute Book Club extract comes from Pilgrimage’s fourth book, The Tunnel, which was published in 1919. Set around 1896, The Tunnel picks up Miriam’s story when she is in her early twenties – Miriam has embarked upon an independent life in London, while trying to process her mother’s tragic recent suicide. In The Tunnel, Miriam has taken on a job as an assistant at a dentist’s surgery on Wimpole Street – at one point in the extract she recalls one of the dentists, Mr Orly, singing a song earlier in the day. The extract itself joins Miriam in the part of a day when she has just left work.

At the beginning of the extract, Miriam is worn out from work, and distracted by the things she sees in the busy city around her: a rush of lighted shops and the remnants of rush-hour traffic surround her; certain side-streets remind her of Bob Greville, a man who has tried to court her; a surprise glimpse of some men fighting proves to be an alarming sight. Life in the Victorian city, it seems, is in many respects no different to its twenty-first-century equivalent. Like many a tired commuter today too, it occurs to Miriam that she should perhaps have a bite to eat. She looks for and fortunately finds a branch of A.B.C. – an affordable café chain that was a familiar sight in London at the turn of the century. The extract ends as Miriam settles down to her meal, thinking about the city she lives in, her place within it, and the complex sense of freedom it gives her.

In the extract, we can see what the novelist and philosopher May Sinclair meant when she said of Richardson’s work that ‘Nothing happens. It is just life going on and on. It is Miriam Henderson’s stream of consciousness going on and on’. Like her fellow modernists James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, Richardson wanted to find a way for the novels she wrote to express inner life not just for the sake of it, but because she believed that modern life shaped people’s mental experiences in distinctive and new ways. We can orient ourselves in the extract by way of the range of familiar London place-names that Miriam sees and reflects upon. But for Richardson, the true experience of the city can’t be boiled down to a map or a series of landmarks. Miriam’s London is a barrage of sensory experiences; those sensations in turn trigger anticipations and memories, gut responses and philosophical reflections. It is also a distinctly gendered space. The word ‘men’ appears six times in the first paragraph of the extract, an oppressive refrain that weighs on the reader, showing how Miriam is in a multitude of different ways reminded that the city is experienced differently for men and women, and often to the detriment of women.

—Adam Guy

The Tunnel

This text comes from the 1919 Duckworth edition of Richardson’s The Tunnel. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Estate of Dorothy Richardson.

When she came to herself she was in the Strand. She walked on a little and turned aside to look at a jeweller’s window and consider being in the Strand at night. Most of the shops were still open. The traffic was still in full tide. The jeweller’s window repelled her. It was very yellow with gold, all the objects close together and each one bearing a tiny label with the price. There was a sort of commonness about the Strand, not like the cheerful commonness of Oxford Street, more like the City with its many sudden restaurants. She walked on. But there were theatres also, linking it up with the west-end and streets leading off it where people like Bob Greville had chambers. It was the tailing off of the west-end and the beginning of a deep dark richness that began about Holywell. Mysterious important churches crowded in amongst little brown lanes ... the little dark brown lane.... She wondered what she had been thinking since she left Wimpole Street and whether she had come across Trafalgar Square without seeing it or round by some other way. They were fighting; sending out suffocation and misery into the surrounding air ... she stopped close to the two upright balanced threatening bodies, almost touching them. The men looked at her. ‘Don’t’ she said imploringly and hurried on trembling.... It occurred to her that she had not seen fighting since a day in her childhood when she had wondered at the swaying bodies and sickened at the thud of a fist against a cheek. The feeling was the same to-day, the longing to explain somehow to the men that they could not fight.... Half-past seven. Perhaps there would not be an A.B.C. so far down. It would be impossible to get a meal. Perhaps the girls would have some coffee. An A.B.C. appeared suddenly at her side, its panes misty in the cold air. She went confidently in. It seemed nearly full of men. Never mind, city men; with a wisdom of their own which kept them going and did not affect anything, all alike and thinking the same thoughts; far away from anything she thought or knew. She walked confidently down the centre, her plaid-lined golf-cape thrown back her small brown boat-shaped felt hat suddenly hot on her head in the warmth. The shop turned at a right angle showing a large open fire with a fireguard, and a cat sitting on the hearthrug in front of it. She chose a chair at a small table in front of the fire. The velvet settees at the sides of the room were more comfortable. But it was for such a little while to-night and it was not one of her own A.B.Cs. She felt as she sat down as if she were the guest of the city men and ate her boiled egg and roll and butter and drank her small coffee in that spirit-gazing into the fire and thinking her own thoughts unresentful of the uncongenial scraps of talk that now and again penetrated her thoughts; the complacent laughter of the men amazed her; their amazing unconsciousness of the things that were written all over them.

The fire blazed into her face. She dropped her cape over the back of her chair and sat in the glow; the small pat of butter was not enough for the large roll. Pictures came out of the fire, the strange moment in her room, the smashing of the plaque, the lamplit den; Mr. Orly’s song, the strange rich difficult day and now her untouched self here, free, unseen and strong, the strong world of London all round her, strong free untouched people, in a dark lit wilderness happy and miserable in their own way, going about the streets looking at nothing, thinking about no special person or thing, as long as they were there, being in London.

Even the business people who went about intent, going to definite places were in the secret of London and looked free. The expression of the collar and hair of many of them said they had homes. But they got away from them. No one who had never been alone in London was quite alive.... I’m free—I’ve got free—nothing can ever alter that she thought, gazing wide-eyed into the fire, between fear and joy. The strange familiar pang gave the place a sort of consecration. A strength was piling up within her. She would go out unregretfully at closing time and up through wonderful unknown streets, not her own streets till she found Holborn and then up and round through the Squares.

Some themes and questions to consider

-

Stream of Consciousness? Though Pilgrimage is often said by critics to represent Miriam Henderson’s ‘stream of consciousness’, Richardson herself disliked the term, arguing that our minds were better described as a pool or an ocean. What word do you think describes the style and content of the extract and why? Does the extract look anything like the way your mind works?

-

The City. Many writers of Richardson’s time sought to depict the complexity of the modern city. Some were critical of the city, seeing it as a decadent and alienating space. Others, though, were thrilled by the opportunities it offered for new perceptions, encounters, and experiences. How does Richardson judge the city in this extract?

-

Dot dot dot. Richardson sought to innovate with punctuation, believing it to be the key to making prose writing more expressive than it was conventionally considered to be. Her ellipses were a favourite device. Do they add anything to this extract? What do you think they express? Why does Richardson alternate between three and four dots?

Full text

The full text of The Tunnel is available via Project Gutenberg.

Connections

If you’re looking for a longer reading experience, you could bring this text alongside the stream of consciousness narration in the extract from Ulysses by James Joyce, which was featured in Season 1.

Resources

Official Dorothy Richardson website

This official author website for Dorothy Richardson introduces her life and work.

Dorothy Richardson Online Exhibition

This website includes scans of Richardson’s handwritten letters – as well as a hilarious experiment with a typewriter. The letters offer a unique insight into different elements of her life as a writer.

Reading Pilgrimage

Detailed resource on Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage, which includes plot summaries, historical information, and explanatory notes.

Pilgrimage Together discussion

In 2022, Brad Bigelow of Neglected Books established Pilgrimage Together, an online reading group that took on a novel of Pilgrimage each month. The Neglected Books YouTube channel archives the monthly discussion session on each of Pilgrimage’s thirteen novels; every video begins with an introduction by a Richardson expert.

Wikipedia introduction to Modernism

To understand Richardson’s work, it is useful to also understand modernism. Wikipedia gives as good an introduction as any to this complex and important cultural phenomenon.

About the Contributor

Adam Guy is a Departmental Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature in the English Faculty at the University of Oxford. He is one of the editors of the Oxford Edition of the Works of Dorothy Richardson.