Speech from ‘The Book of Sir Thomas More’, attributed to Shakespeare

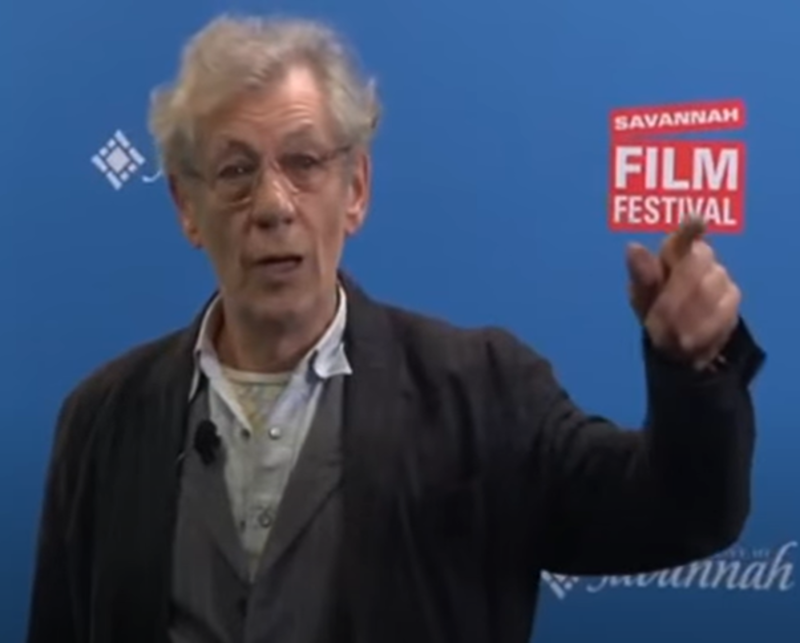

A screengrab of Sir Ian McKellen performing the speech from ‘Sir Thomas More’ at the Savannah Film Festival

[Screengrab from YouTube]

Many people think this speech was written by Shakespeare to help get a script written by a number of fellow playwrights into a stageworthy state, probably around 1603–4. It’s from an unpublished play called ‘Sir Thomas More’, which has lots of different episodes including, most controversially, a sequence in which English Londoners turn on their foreign neighbours in an anti-migrant (the Elizabethan word is ‘alien’) riot. The authorities in Elizabethan London were worried about copycat behaviour, so the censor, the Master of the Revels, intervened with suggestions about toning down the violence.

What’s most remarkable about this speech is More’s rhetoric: he quells the rioters by encouraging them to think of themselves as refugees, banished from England by their behaviour, and forced to live by the kindness of strangers. ‘How would you like it?’ More asks, ‘What would you think to be us’d thus?’

The idea of putting yourself in the someone else’s shoes has value today more than ever, perhaps – attitudes to the thousands of people who undertake the terrifying journey to Britain in small boats often seem to lack this fundamental human empathy. But it’s also an interesting speech to put alongside other works by Shakespeare. Of course, in The Merchant of Venice and in Othello, Shakespeare addresses directly the outsider or alien who is tolerated but mistrusted by the host community. Both plays highlight a single individual – Shylock the Jewish moneylender and Othello the Moorish (the word has a range of resonances but its primary meaning is ‘Muslim’) general – and show how they are turned from an individual into a stereotype or caricature by the characters in their play (and perhaps by the plays themselves). Some of the language – including of dogs and the nature of ‘barbarous’ – is echoed in these other plays. More’s speech in ‘Sir Thomas More’ offers a kind of manifesto for what is implicit, sometimes contradicted, elsewhere in the canon.

This extract also helps us to think a bit differently about Shakespeare as a writer. We have inherited, along with our reverence for his works, an elevated sense of his poetic calling. If you’re studying a play for an exam, you’re probably poring over every word and comma, giving them all significance and kinds of intentionality. But this document shows how plays were really put together. It reminds us that playwrighting, a term originally coined as an insult, suggests not ‘writing’ but ‘wrighting’: the same artisanal activity as that of shipwrights or wheelwrights, who take materials and shape them, rather than inventing them out of nowhere. And it shows us someone who was less invested, perhaps, in the coherence and single vision of a play, and more willing to contribute to the collective enterprise of theatre. We used to think that Shakespeare only collaborated with other (and inevitably lesser) authors at the beginning and end of his career, first as a kind of apprentice and then as the maestro. But ‘Sir Thomas More’ is in the middle, showing that the writer of, most recently, Twelfth Night and Othello was also contributing to other scripts. Both the sentiment of Thomas More’s speech, then, and the insight it gives us into the contingent world of putting a play together at the beginning of James I’s reign, mean it is well worth a look.

—Emma Smith

The Book of Sir Thomas More

You’ll put down strangers,

Kill them, cut their throats, possess their houses,

And lead the majesty of law in lyam [leash]

To slip him like a hound; alas, alas, say now the King,

As he is clement if th’offender mourn,

Should so much come too short of your great trespass

As but to banish you: whither would you go?

What country, by the nature of your error,

Should give you harbour? Go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, Spain or Portugal,

Nay, anywhere that not adheres to England,

Why, you must needs be strangers, would you be pleas’d

To find a nation of such barbarous temper

That breaking out in hideous violence

Would not afford you an abode on earth.

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owed not nor made not you, not that the elements

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But charter’d unto them? What would you think

To be us’d thus? This is the strangers’ case

And this your mountainish inhumanity.

Some themes and questions to consider

-

How might this speech echo other moments of empathy from your reading?

-

Is More’s speech here a bit too ‘preachy’? Are there disadvantages to literary works that seem to tell us what to think?

-

Does this speech, and what you’ve learned about how it was written, change the way you think of Shakespeare?

Full text

The full text of ‘Thomas More’ can be read at Project Gutenberg.

Connections

If you’re looking for a longer reading experience you could bring this text alongside The Entertainment at Britain’s Burse by Shakespeare’s contemporary Ben Jonson, which also engages with the presence of the outside world within England, though from a different angle.

Resources

The British Library Thomas More pages

These images from the manuscript may well be (there is disagreement on this) the only extensive piece of Shakespeare’s handwriting in existence. Even if they are not, this messy, working document gives a real insight into the practicalities of playwrighting, in contrast to the stately annotated printed texts in which we usually encounter this material.

Ian McKellen performs the speech

Watch Sir Ian McKellen perform the speech at the Savannah Film Festival.

Royal Shakespeare Company production of ‘Thomas More’

View images of the RSC’s 2005 production of the play.

Keywords of Identity, Race and Human Mobility in Early Modern England

This open access publication from the TIDE project explores terminologies and identities in ways that illuminate categories such as stranger, Jew, and Turk.

‘Not at Home’ Shakespeare and migration

In this piece I quote the More speech in the context of thinking about Twelfth Night as a story about migration.

About the Contributor

Emma Smith is Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Hertford College, Oxford, and the author of This Is Shakespeare (2019). Her lectures on Shakespeare are available at the University of Oxford Podcasts.