Echolocations: Reflections on Poems by A.E Stallings (Issue 4)

Two poems from the Summer 2025 issue of Nimrod

In this series, A.E. Stallings, Oxford’s Professor of Poetry, will explore a contemporary poem from a new book or anthology or journal and explain what she admires about it. This issue explores two poems from the Summer 2025 issue of Nimrod: Curse the Mediterranean, my Enemy by Jonny Teklit and Eulogy for Dada (Who Loved to Waltz) by M. I. Devine. Subscribe to the newsletter to receive each issue in your inbox.

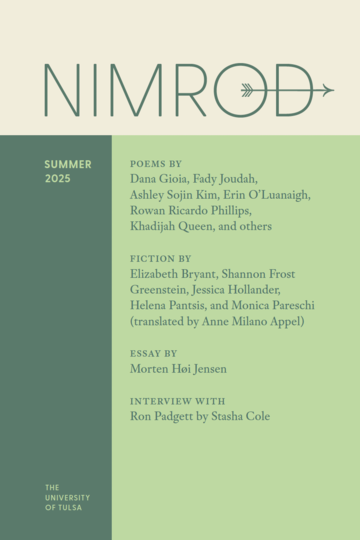

Nimrod, the international literary journal out of the University of Tulsa (nimrod.utulsa.edu), has a storied history: founded in 1956, it boasts of having published writers such as W.H. Auden, Mahmoud Darwish, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Mark Strand, among others. My sense is it had faded into the background somewhat in recent decades (certainly, it was not on my radar), but with the advent of a new editor, the wildly talented and productive poet, critic, and translator Boris Dralyuk (lately of Los Angeles, see his terrific debut My Hollywood), the journal is back with a vengeance, a mighty hunter once again.

Two poems from the Summer 2025 issue I recently saw online knocked my socks off. That’s a pretty good ratio for any magazine, and I have yet to lay eyes on the physical object. Also, and here is another good sign I think, they are both by poets new to me.

I encountered “Curse the Mediterranean, My Enemy” online on world refugee day (June 20th), and it caught my eye with its title and subject matter. I am based in Greece, and have run a poetry workshop for the past decade with refugee women, many of whom have experienced the terrifying sea-crossing that has for so many ended in death. So naturally I perked up a little, and paused my day to read this poem:

Curse the Mediterranean, my Enemy

by Jonny Teklit

to every Eritrean who has perished on their

journey across the Mediterranean

Curse the Mediterranean, my enemy.

The sea has swallowed so many of my people

on their way to find a life worth enduring

the sneers of smugglers, the breaking of ships.

The sea has swallowed so many of my people.

I swim laps at the community pool and imagine them:

the sneers of smugglers, the breaking of ships,

a life with just a cup more gentleness. They aren’t greedy.

I swim laps at the community pool and imagine them

on their way to find a life worth enduring,

a life with just a cup more gentleness. They aren’t greedy.

Curse the Mediterranean, my enemy.

I read it a few times, admiring its natural deployment of meditative and rhetorical repetition, its plain-spoken yet flexible register that could include “the breaking of ships” (which would not be out of place in a fine literary translation of the Odyssey) and the down-to-earth “laps at the community pool,” before I belatedly realized that this was also a deft pantoum. (A pantoum is a Malaysian form that braids repeating lines, and ends by coming back around to the opening. I think French poets popularized it in the west, and then Francophile poets such as Seferis in Greek or Ashbery in English.)

Something about the way the thoughts unspool, from the solemn curse of the first sentence, to the sad factual statement of the second, and its elaboration in the third and fourth, before it takes a rather startling turn in line six with the laps in the community pool, how it folds and unfolds itself, distracted me from the form itself. The twelve-line poem consists of only six original lines, and yet covers (or overlaps) a vast space of situation and geography, a wide range of sympathy and antipathy (to the Mediterranean, but really of course to those who permit this to happen), of situation from extreme peril to banal safety. Swimming, the poet imagines the drowning and the drowned. Something about swimming laps, the way you go back and forth over the same tiled floor, kicking and breathing, thinking and moving, moving and thinking, breathing and kicking, makes the form the perfect fit for this stark condemnation of our collective indifference to the suffering of others, a “political” poem that does not feel like a screed, but a stream of consciousness. I read in his bio that Teklit is working on his debut collection—one clearly to look out for.

A second Nimrod poem I came across more recently delighted me with its formal sure-footedness as well, but also its ease with allusion and reference, while somehow being more than the sum of its pastiche. It’s a neat trick! How does the poet do it?

Eulogy for Dada (Who Loved to Waltz)

by M. I. Devine

My father moved through moods of love. Wait, no.

Dooms. My father moved through dooms of shove.

Of push and pull. And not enough.

When he was old and gray and changing his own tires—

I mean, fire. When he was old and gray that’s when he was fired.

He was full of sleep and not enough.

He made banked fires blaze. No, no

One ever thanked him. He moved

Out and that was thanks enough.

He beat time on my head.

In lieu of a metronome. In lieu of flowers, he said

Words but words, in lieu of flowers, are not enough.

He might have danced in a green bay, who knows, hard to say. O, no

Question he raged. Off the cuff

His last words were perfect and enough:

Re: the dying of the light, he said, and I quote—wait, no.

(Spoiler alert! I will flag most of the allusions.) Some of the poems it breezily refers to or nods at include the deliciously lugubrious “My father moved through dooms of love” of E. E. Cummings, Yeats’s loose adaptation of Ronsard, “When You are Old” (a love poem rather than a father poem, technically, I’d say), Robert Hayden’s ineffably perfect “Those Winter Sundays,” Theodore Roethke’s brilliantly off-kilter “My Papa’s Waltz,” and of course the most famous villanelle in the language, “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas.

I would be hard put to describe the “form” of this cento-ish poem exactly—a curtal villanelle? Certainly, it is villanelle adjacent. (If there is a term for this, let me know!) Another type of poet would have regularized it, but I like the flirtation with form here. At any rate, it is very attractive in the way it moves through the doomed father love, with an elegant swerving and recalibrating, like a nimble tap-dancer pretending to be drunk in some classic Hollywood film.

“Dooms of love” morphs into “moods of love” and then “dooms of shove”—a worrisome direction. “Not enough” in the context of being fired is devastating, and a surprising shift. There is a moment where the father briefly becomes the noble father of Hayden’s poem, only to move out, thankfully. The father beats time on the speaker’s head, like Roethke’s father, but the metronome gives out; “in lieu of flowers” seems to foreshadow a death. The ending confirms this (as does the title, of course), and resists the imperative resistance of Thomas’s poem. But there is a moment of grace (“not enough” turns into “perfect and enough”), and the last words, with their knowing wink of “and I quote” (re: the dying of the light), become that “wait, no” which feels abruptly abbreviated, the cliff of grief.

Perhaps this is intended as exceptionally clever and original (for all its borrowing) light verse. I couldn’t say whether this poet is speaking of their own father, whether this poem is “real” as well as “true.” (The Dadaish pun of the title mitigates against my reading, I realize.) It’s sharp, it’s quirky, it’s funny. Yet I was also moved, and somehow the poet’s ringing the rapid changes on these allusions of anthology poems did not diminish this feeling, but perhaps deepened the resonance. In fact, I realize, I write this on the eve of the 25th anniversary of my own father’s death. His last words, apparently (I was an ocean away), as he was taken to hospital were his usual background concern with thrift: “Turn off the light.” Wait, no.

AES

Poems published with permission from the poets and Nimrod International Journal, where the poems originally appeared.