Modern Love by George Meredith

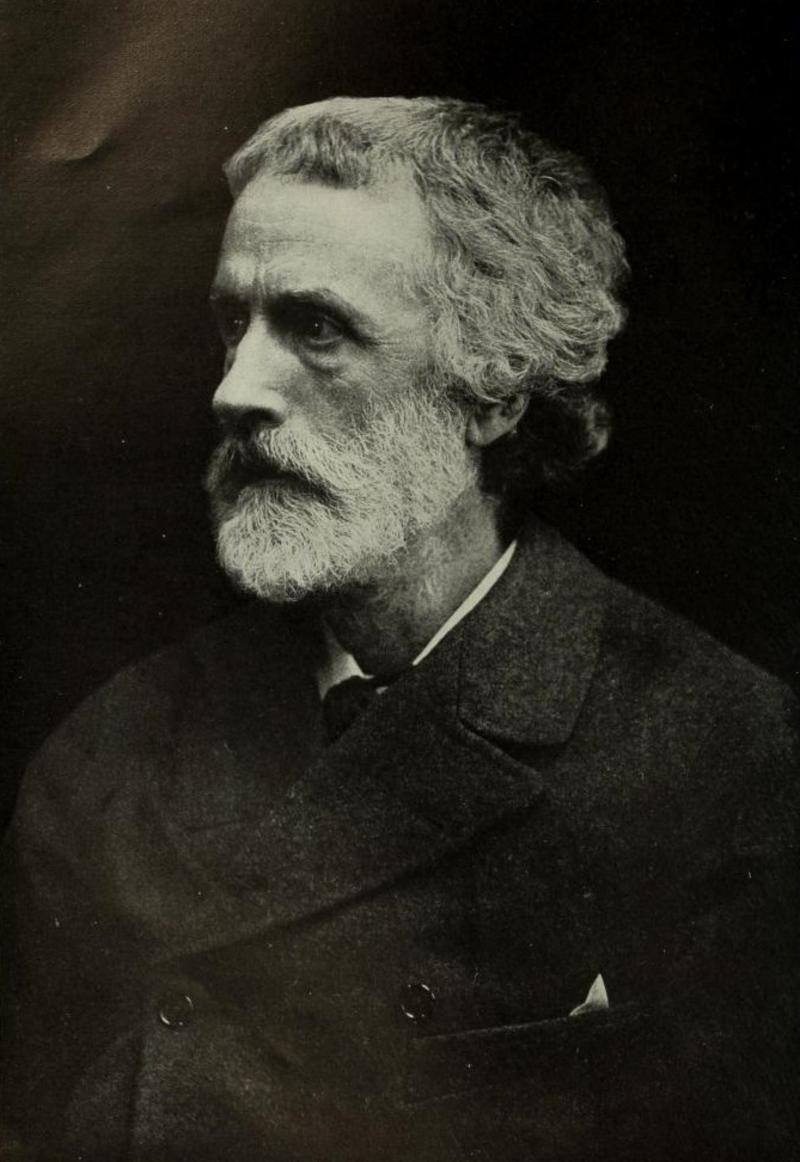

This extract comes from George Meredith’s Modern Love, a sequence of fifty sonnets published in 1862. Meredith was primarily a Victorian novelist, but he also wrote poetry, and Modern Love is widely accepted as his most important poetic achievement.

The poet’s aim in this work is to pick apart the idealised image of love that circulates in Victorian poetry. His images of corpses, ghosts, and skeletons are perhaps unexpected for what appear to be love sonnets. Indeed, contemporary reviewers were outraged by Meredith’s depiction of love, using the language of ‘disease’, rot, and vulgarity. Meredith himself engaged with this vocabulary, as he described his poem as ‘a dissection of the sentimental passion of these days’: ‘dissection’ is a medical image which evokes the visceral body.

The two sonnets here depict different domestic scenes: the first, private, as two lovers sit together by a fireplace; the second, shared, as they host a dinner party. In both, as throughout the sequence, love is fraught, reflecting the fact that the narrator has found out about his wife’s infidelity. The adjective ‘shipwreck’d’ in the first sonnet evokes destruction and ruin, and the image of a ‘chasm’, which the lovers witness in the fire but which also expands to describe their relationship, suggests that they have become distant. The line ‘[s]he yearn’d to me that sentence to unsay’ portrays their difficulties in communicating, and their desire to return to a previous time, through the prefix ‘un’ in ‘unsay’. In the second sonnet, Meredith engages with the contrast between the surface and depth of love, using watery language of ‘buoyancy’ and ‘deeps’. That sonnet begins with an image of ultimate cheerfulness, but this joy is haunted by a ‘ghost’, which recurs as ‘THE SKELETON’, ‘devils’, and then ‘corpse-light’ in the final line. This compound noun is typical of Meredith’s poetic style throughout the sequence, as he searches for new language to capture the complexity of the love he portrays.

Meredith draws on a tradition of sonnet-writing, as championed most famously by the late medieval Italian poet Petrarch and later by Shakespeare, amongst many others. The sonnet form was undergoing a revival in the Victorian period. It is striking that Meredith’s sonnets, as well as experimenting with the traditional use of this form, which often spoke of unrequited or yearning love, also play with the rules of the form itself: they contain sixteen lines rather than fourteen! We can wonder why Meredith extends the length in this way. Does it reflect his desire to present the full complexity of love? Does it show him waging war on traditional literary forms as he seeks a new way of expressing his ideas? Meredith’s poetic project is experimental and puzzling.

—Iris Pearson

Modern Love

These two sonnets are taken from the middle of the poem. The narrator has discovered that his wife has been unfaithful, and here he narrates two separate scenes in their relationship.

XVI

In our old shipwreck’d days there was an hour,

When in the firelight steadily aglow,

Join’d slackly, we beheld the chasm grow

Among the clicking coals. Our library-bower

That eve was left to us: and hush’d we sat

As lovers to whom Time is whispering.

From sudden-open’d doors we heard them sing:

The nodding elders mix’d good wine with chat.

Well knew we that Life’s greatest treasure lay

With us, and of it was our talk. ‘Ah, yes!

‘Love dies!’ I said: I never thought it less.

She yearn’d to me that sentence to unsay.

Then when the fire domed blackening, I found

Her cheek was salt against my kiss, and swift

Up the sharp scale of sobs her breast did lift:—

Now am I haunted by that taste! that sound!

XVII

At dinner she is hostess, I am host.

Went the feast ever cheerfuller? She keeps

The Topic over intellectual deeps

In buoyancy afloat. They see no ghost.

With sparkling surface-eyes we ply the ball:

It is in truth a most contagious game;

HIDING THE SKELETON shall be its name.

Such play as this the devils might appal!

But here’s the greater wonder; in what we,

Enamour’d of our acting and our wits

Admire each other like true hypocrites.

Warm-lighted glances, Love’s Ephemerae,

Shoot gaily o’er the dishes and the wine.

We waken envy of our happy lot.

Fast, sweet, and golden, shows our marriage knot.

Dear guests, you now have seen Love’s corpse-light shine!

Some themes and questions to consider

-

How does Meredith engage with the contrast between appearances and reality? (Think about the language of ‘sparkling surface-eyes’ and ‘buoyancy’.)

-

How does the depiction of their love subtly change within each sonnet, and between the two?

-

As well as adapting the sonnet form, how does Meredith make use of rhyme in these poems? (Think about which words he connects by rhyming them: are these surprising? What is the effect of this surprise?)

Full text

The full text of Modern Love is available from the Internet Archive.

Connections

If you’re looking for a longer reading experience, you could bring this text alongside the amatory scenes from The Knight’s Tale in Season 1.

More on Meredith and Modern Love

The Victorian Web

A set of resources about the life, context and works of George Meredith.

A contemporary review of Modern Love

This review was written by R.H. Hutton and is accessible via a free subscription to the Spectator archive.

The sonnet form

Stephen Regan, ‘The Victorian Sonnet, from George Meredith to Gerard Manley Hopkins.’

This article looks at nineteenth-century innovations in sonnets.

Natalie M. Houston, ‘Affecting Authenticity: Sonnets from the Portuguese and Modern Love.’

This article discusses emotion and the love sonnet in the nineteenth century.

Learning the Sonnet

Rachel Richardson’s ‘history and how-to guide’ on the sonnet for the Poetry Foundation, which includes Meredith in its scope.

About the Contributor

Iris Pearson is a DPhil student at New College, working on form and affect (feeling) in late twentieth-century novels. She is interested in how writers use form to manipulate the reader’s experience of their texts, and thinks about the value of paying attention to the formal qualities of literary works. She also works on Spanish American literature, and has published an article on two Argentine novelists in Paris for the Latin American Literary Review (2021).