The legends of Mermaids: In folklore, anonymous Ballads, and the work of Rivers Solomon and Monique Roffey

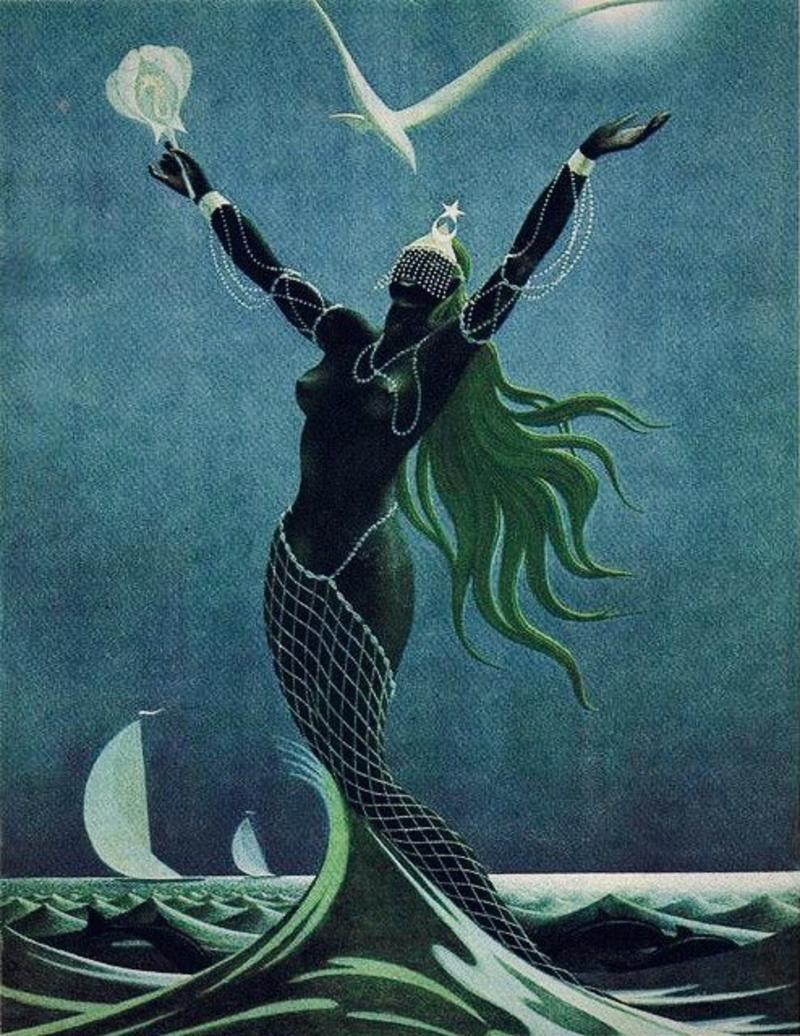

Artist's depiction of Mami Wata

[Artist unknown; all attempts were made to trace the copyright holder]

A note on the term Creole

Creole is often simply used to refer to all people who are part of Caribbean culture, irrespective of race, but it can also mean a language that developed through the contact of a European language with the languages of indigenous or enslaved peoples and, by extension, a culture formed by contacts between European and culture/s of indigenous or enslaved peoples.

Because of the Disney animated film, The Little Mermaid, we may feel inclined to think of mermaids as an appropriate subject for children. But it was, in fact, never thus, and folktales involving mermaids rarely have happy endings.

In popular culture, mermaids were ill-omened. The European ballad ‘The Mermaid’ (Child Ballad #289), excerpted here, dates back at least to the mid-1700s. It is also known as ‘Waves on the Sea’ and ‘The Wrecked Ship’. As the ballad indicates, the sight of a mermaid was a portent of a shipwreck. As soon as she is spotted, the entire crew give up hope, and the ballad ends with the ship sinking to the bottom of the sea. She herself does nothing whatsoever; her very existence is a portent of a storm.

The silkies of the Hebrides and Orkney Islands are also part seal and part human, although in their case, the sealskin covers their human skin completely, so that their liminality [being both–and] is not visible. In a traditional Orkney ballad, a silkie male enchants a human woman. The ballad warns:

When he be man, he takes a wife,

When he be beast, he takes her life.

Ladies, beware of him who be –

A silkie come from Skule Skerrie.

In folklore if a girl went missing while out on the ebb, or at sea, it was said that her silkie lover had taken her to his watery domain.

This week’s readings also contain extracts from two more recent books are about mermaids, and they too are not for children. Their mission is to unearth the dark and frightening aspects of human engagements with the sea. Both are written from a perspective of otherness to a normative white Western point of view – Rivers Solomon is non-binary and is linked to the African diaspora of slavery; Monique Roffey is Tobagan, and her mermaids survive as the testament of the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, destroyed by colonialism. And yet this otherness is what allows both these writers to see something that was always present in the mermaid. Mermaids are themselves a mixture, both human and not. This makes them especially apt as images of the Creole post-slavery and postcolonial world. Vaughn Scribner writes:

according to culturally constructed perceptions, biases and worldviews, merpeople are … at once familiar and foreign, human and monster. This very liminality seems to encourage homogeneity more than disparity, as various cultures continuously absorb and assimilate these strange creatures.

In their novella The Deep, Rivers Solomon explores the idea that an entire people has been born from a relationship between the ocean and the oceanic bodies of the pregnant enslaved women thrown overboard by the slave traders. These mermaid-like descendants of humans – the wajinru – share in Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid’s relationship to violence. But just as Andersen’s Little Mermaid is a victim of violence who refuses in the end to perpetrate it, so too this new aquatic people do not choose revenge, but want to save and redeem the vulnerable humans who cannot survive in the rising seas. The story was inspired by a hip-hop track created by Clipping, who are credited as co-authors:

Our mothers were pregnant African women

Thrown overboard while crossing the Atlantic Ocean on slave ships

We were born breathing water as we did in the womb

We built our home on the sea floor

Unaware of the two-legged surface dwellers

Until their world came to destroy ours

With cannons, they searched for oil beneath our cities

Their greed and recklessness forced our uprising

With a song as its beginning, The Deep works as a kind of narrative memorial, which celebrates the power of song and story to offer a maternal healing of historical traumas in mysterious below-the-surface ways The main character is called Yetu, in some African languages a word for father, and in others the word for our, but Yetu is neither father nor mother; rather, she is the collective memory of a people; our memory is so dreadful that it can hardly be carried.

Monique Roffey’s The Mermaid of Black Conch explores the tricky relationship between the peoples of the Caribbean and the sea that surrounds them. Aycayia, a centuries old mermaid cursed to roam the sea by jealous wives, befriends a lazy fisherman called David. Soon, however, the frightening masculinity of a Hemingway-esque fisherman enters the scene; the fisherman sees her simply as plunder. The trace of doomed love in the traditional mermaid and silkie tales finds an echo in Roffey’s novel, and so does the uncomfortable sense that these beings represent unruly desire.

In this short extract, the fisherman David reacts to Aycayia with a human recognition of the divine that could apply to a number of Caribbean belief systems, and therefore reminds us of mermaid hybridity: ‘“Mother of Holy God on earth,” he exclaimed. “Ayyy,” he called across the water. “Dou dou. Come. Mami wata! Come. Come, nuh.”’ The merwoman, as Roffey calls her, does not respond to these magical names (but see the Learn More tab for what they mean). In a deliberate reversal of roles, it is David’s song that attracts the mermaid to him. The attraction is fatal, as it always is.

The music brought her to him, not the engine sound, though she knew that too. It was the magic that music makes, the song that lives within every creature on earth, including mermaids. She hadn’t heard music for a long time, maybe a thousand years, and she was irresistibly drawn up to the surface, real slow and real interested.

—Diane Purkiss

Contents

Child Ballad 289

Extract from The Deep by Rivers Solomon

Extract from The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey

Child Ballad 289

289C.1 ONE Friday morn as we’d set sail,

And our ship not far from land,

We there did espy a fair mermaid,

With a comb and a glass in her hand, her hand, her hand,

With a comb and a glass in her hand.

While the raging seas did roar,

And the stormy winds did blow,

And we jolly sailor-boys were up, up aloft,

And the landsmen were lying down below,

And the landlubbers all down below, below, below,

And the landlubbers all down below.

289C.2 Then up spoke the captain of our gallant ship,

Who at once did our peril see;

I have married a wife in fair London town,

And tonight she a widow will be.’

289C.3 And then up spoke the litel cabin-boy,

And a fair-haired boy was he;

‘I’ve a father and mother in fair Portsmouth town,

And this night she will weep for me.’

289C.4 Now three times round goes our gallant ship,

And three times round went she;

For the want of a life-boat they all were drownd,

As she went to the bottom of the sea.

The Deep

“IT WAS LIKE DREAMING,” SAID Yetu, throat raw. She’d been weeping for days, lost in a remembering of one of the first wajinru.

“Then wake up,” Amaba said, “and wake up now. What kind of dream makes someone lurk in shark-dense waters, leaking blood like a fool? If I had not come for you, if I had not found you in time…” Amaba shook her head, black water sloshing over her face. “Do you wish for death? Is that why you do this? You are grown now. Have been grown. You must put those childish whims behind you.” Amaba waved her front fins forcefully as she lectured her daughter, the movements troubling the otherwise placid water.

“I do not wish for death,” said Yetu, resolute despite the quiet of her worn voice.

“Then what? What else would make you do something so foolish?” Amaba asked, her fins a bevy of movement.

Yetu strained to feel Amaba’s words over the chorus of ripples, her skin drawn away from the delicate waves of speech and toward the short, powerful pulses brought on by her amaba’s gesticulations.

“Answer me!” Amaba said, her tone desperate and screeching.

Most of the time, Yetu kept her senses dulled. As a child, she’d learned to shut out what she could of the world, lest it overwhelm her into fits. But now she had to open herself back up, to make her body a wound again so Amaba’s words would ring against her skin more clearly.

Yetu closed her eyes and honed in on the vibrations of the deep, purposefully resensitizing her scaled skin to the onslaught of the circus that is the sea. It was a matter of reconnecting her brain to her body and lowering the shields she’d put in place in her mind to protect herself. As she focused, the world came in. The water grew colder, the pressure more intense, the salt denser. She could parse each granule. Individual crystals of the flaky white mineral scraped against her.

Even though Yetu always kept herself tense against the ocean’s intrusions, they found their way in; but with her senses freshly unreined, the rush of feeling was dizzying. This was nothing like the faraway throbbing she’d grown used to when she threw all her energy into repelling the world outside. The push and pull of nearby currents upended her. The flutter of a school of fangfish reverberated deep in her chest. How did other wajinru manage this all the time?

“Where did you go just now? Are you dreaming yet again?” asked Amaba, sounding more defeated than angry. Her voice cracked into splintered waves, rough against Yetu’s skin.

“I am here, Amaba. I promise,” said Yetu quietly, exhaustedly, though she wasn’t sure that was true. Adrift in a memory that wasn’t hers, she hadn’t been present when she’d brought herself to the sharks to be feasted upon. How could she be sure she was here now?

Yetu needed to recover her composure. She’d never done something that dangerous before. She had lost more control of her abilities than she’d realized. The rememberings were always drawing her backward into the ancestors’ memories—that was what they were supposed to do—but not at the expense of her life.

“Come to me,” said Amaba, several paces away. Too weak to argue, Yetu offered no protest. She resigned herself for now to do her amaba’s biddings. “You need medicine, child. And food. When did you last eat?”

Yetu didn’t remember, but as she took a moment to zero in on the emptiness in her stomach, she was surprised to find the pain of it was a vortex she could easily get lost in. She moved her body, examined its contours. She’d been withering away, and now there was little left of her but the base amounts of outer fat she needed to keep warm in the ocean’s deepest waters.

As evidenced by her encounter with the sharks, Yetu’s condition was worsening. With each passing year, she was less and less able to distinguish rememberings from the present.

“Eat these. They will help your throat heal,” said Amaba, drawing her daughter into her embrace. Yetu floated in the dense, black brine, her amaba’s fins a lasso about her torso. “Come, now. I said eat.” Amaba pressed venom leaves into Yetu’s mouth, humming a made-up lullaby as she did. Water waves from her voice stroked Yetu’s scales, and though Yetu usually avoided such stimulation, she was pleased to have a tether to the waking world as her connection to it grew more and more precarious. She needed frequent reminders she was more than a vessel for the ancestors’ memories. She wouldn’t let herself disappear. “Keep chewing. That’s good. Very good. Now swallow.”

Spurred by the promise of pain relief as much as by her amaba’s prodding, Yetu gagged the medicine down. Venom leaves slithered like slime down her throat and into her belly, and with every swallow she coughed.

“See? Isn’t that nice? Can you feel it working in you yet?”

Cradled in her amaba’s front fins, Yetu looked but a pup. It was fitting. In this moment, she was as reliant on Amaba’s care as she had been in infancy. She’d grown from colicky pup into mercurial adolescent into tempestuous adult, still sometimes in need of her amaba’s deep nurturing.

Given her sensitivity, no one should have been surprised that the rememberings affected Yetu more deeply than previous historians, but then everything surprised wajinru. Their memories faded after weeks or months—if not through wajinru biological predisposition for forgetfulness, then through sheer force of will. Those cursed with more intact long-term recollection learned how to forget, how to throw themselves into the moment. Only the historian was allowed to remember.

The Mermaid of Black Conch

David Baptiste’s dreads are grey and his body wizened to twigs of hard black coral, but there are still a few people around St. Constance who remember him as a young man and his part in the events of 1976, when those white men from Florida came to fish for marlin and instead pulled a mermaid out of the sea. It happened in April, after the leatherbacks had started to migrate. Some said she arrived with them. Others said they’d seen her before, those who’d fished far out. But most people agreed that she would never have been caught at all if the two of them hadn’t been carrying on some kind of flirty-flirty behaviour.

*

Black Conch waters nice first thing in the morning. David Baptiste often went out as early as possible, trying to beat the other fishermen to a good catch of king fish or red snapper. He would head to the jagged rocks one mile or so off Murder Bay, taking with him his usual accoutrements to keep him company while he put his lines out—a stick of the finest local ganja and his guitar, which he didn’t play too well, an old beat-up thing his cousin, Nicer Country, had given him. He would drop anchor near those rocks, lash the rudder, light his spliff and strum to himself while the white, neon disc of the sun appeared on the horizon, pushing itself up, rising slow slow, omnipotent into the silver-blue sky.

David was strumming his guitar and singing to himself when she first raised her barnacled, seaweed-clotted head from the flat, grey sea, its stark hues of turquoise not yet stirred. Plain so, the mermaid popped up and watched him for some time before he glanced around and caught sight of her.

“Holy Mother of Holy God on earth,” he exclaimed. She ducked back under the sea. Quick quick, he put down his guitar and peered hard. It wasn’t full daylight yet. He rubbed his eyes, as if to make them see better.

“Ayyy,” he called across the water. “Dou dou. Come. Mami wata! Come. Come, nuh.”

He put one hand on his heart because it was leaping around inside his chest. His stomach trembled with desire and fear and wonder because he knew what he’d seen. A woman. Right there, in the water. A red-skinned woman, not black, not African. Not yellow, not a Chinee woman, or a woman with golden hair from Amsterdam. Not a blue woman, either, blue like a damn fish. Red. She was a red woman, like an Amerindian. Or anyway, her top half was red. He had seen her shoulders, her head, her breasts, and her long black hair like ropes, all sea mossy and jook up with anemone and conch shell. A merwoman. He stared at the spot of her appearance for some time. He took a good look at his spliff; was it something real strong he smoke that morning? He shook himself and gazed hard at the sea, waiting for her to pop back up.

“Come back,” he shouted into the deep greyness. The mermaid had held her head up high above the waves, and he’d seen a certain expression on her face, like she’d been studying him.

He waited.

But nothing happened. Not that day. He sat down in his pirogue and, for some reason, tears fell for his mother, just like that. For Lavinia Baptiste, his good mother, the bread baker of the village, dead not two years. Later, when he racked his brain, he thought of all those stories he’d heard since childhood, tales of half-and-half sea creatures, except those stories were of mermen. Black Conch legend told of mermen who lived deep in the sea and came onto land now and then to mate with river maidens—old-time stories, from the colonial era. The older fishermen liked to talk in Ce-Ce’s parlour on the foreshore, sometimes late into the night, after many rums and too much marijuana. The mermen of Black Conch were just that: stories.

It was April, time of the leatherback migration south to Black Conch waters, time of dry season, of pouis trees exploding in the hills, yellow and pink, like bombs of sulphur, the time when the whoreish flamboyant begins to bloom. From that moment, when that red-skinned woman rose and disappeared as if to tease him, David ached to see her again. He felt a bittersweet melancholy, a soft caress to his spirit. Nothing to do with what he’d been smoking. That day, a part of him lit up, a part he’d no idea was there to light. He had felt a sharp stabbing sensation, right there in the flat part between his ribs, in his solar plexus.

“Come back, nuh,” he said, soft soft and gentlemanlike after his mother-tears had dried and his face was tight with the salt. Something had happened. She had risen from the waves, chosen him, a humble fisherman.

“Come, nuh, dou dou,” he pleaded, this time softer still, as if to lure her. But the water had settled back flat.

*

Next morning, David went to the exact same spot by those jagged rocks off Murder Bay and waited for several hours and saw nothing. He smoked nothing. Day after, the same thing. Four days he went out to those rocks in his pirogue. He cut the engine, threw out the anchor, and waited. He told no one what he had seen. He avoided Ce-Ce’s parlour, the property of his kind-hearted, bigmouth aunt. He avoided his cousins, his pardners in St. Constance. He went home to his small house on the hill, the house he’d built himself, surrounded by banana trees, where he lived with Harvey, his pot hound. He felt on edge. He went to bed early so as to rise early. He needed to see the mermaid again, to be sure that his eyes had seen correctly. He needed to cool what had become an inflammation in his heart, to pacify the buzz that had started up in his nervous system. He had never had this type of feeling, certainly not for no mortal woman.

Then, day five, around six o’clock, he was strumming his guitar, humming a hymn, when the mermaid showed herself again. This time she splashed the water with one hand and made a sound like a bird squeak. When he looked up he didn’t frighten so bad, even though his belly clenched tight and every fibre in his body froze. He stayed still and watched her good. She was floating port side of his boat, cool cool, like a regular woman on a raft, except there was no raft. The mermaid, with long black hair and big, shining eyes, was taking a long suspicious look at him. She cocked her head, and it was only then David realised she was watching his guitar. Slow slow, so as not to make her disappear again, he picked it up and began to strum and hum a tune, quietly. She stayed there, floating, watching him, stroking the water, slowly, with her arms and her massive tail.

The music brought her to him, not the engine sound, though she knew that too. It was the magic that music makes, the song that lives within every creature on earth, including mermaids. She hadn’t heard music for a long time, maybe a thousand years, and she was irresistibly drawn up to the surface, real slow and real interested.

That morning David played her soft hymns he’d learnt as a boy, praising God. He sang holy songs for her, songs which brought tears to his eyes, and there they stayed, on this second meeting, a small patch of sea apart, watching each other—a young, wet-eyed Black Conch fisherman with an old guitar, and a mermaid who’d arrived on the currents from Cuban waters, where once they talked of her by the name of Aycayia.

Some themes and questions to consider

-

Both these books are about buried history. How successful are they in making the readers aware of that history?

-

These modern mermaids are not pretty, but frightening. Why do you think that is the case? What are the gains and losses of this kind of depiction?

-

What do you think these books are saying about gender?

-

Can we share these stories even if we don’t share the history that prompted them?

Full texts and published excerpts

The Child Ballad

Versions of the Child ballad may be found at the Internet Sacred Text Archive and Contemplator.

Watch the ballad in sung performance by Daniel Kelly Folk Music.

‘The Little Mermaid’

The Hans Christian Andersen story, ‘The Little Mermaid’, can be read on Sur La Lune.

The Deep

Find out more about The Deep (2019) by Rivers Solomon on Simon & Schuster’s page for the book, or purchase it via Bookshop.

Listen to the original track ‘The Deep’, by the experimental hip-hop group Clipping.

The Mermaid of Black Conch

Find out more about The Mermaid of Black Conch (2020) by Monique Roffey on Peepal Tree’s page for the book, or purchase it via Bookshop.

Connections

Mary Prince and Olaudah Equiano (Season 1) both describe frightful sea voyages in their narratives of enslavement. Equiano describes the trauma of the Middle Passage in his full text.

The authors

Rivers Solomon

Solomon is non-binary and intersex and states that they use fae/faer and they/them pronouns. They describe themselves as ‘a dyke, an anarchist, a she-beast, an exile, a shiv, a wreck, and a refugee of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.’

As of 2018, Solomon lives in Cambridge, UK, with their family. Originally from the United States, they received their BA in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity from Stanford University in California and an MFA in Fiction Writing from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin. They grew up in California, Indiana, Texas, and New York. Their literary influences include Ursula Le Guin, Octavia Butler, Alice Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, Ray Bradbury, Jean Toomer, and Doris Lessing. The Deep won the 2020 Lambda Award and was shortlisted for the Nebula, Locus, and Hugo awards.

Monique Roffey

Monique Roffey was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, in 1965, to an English father and mother of French, Italian, Maltese and Lebanese descent. Roffey was educated at St Andrew's School in Maraval, Trinidad, and then in the UK at St Maur's Convent, and St George's College, Weybridge. She graduated with a BA in English and Film Studies from the University of East Anglia in 1987, and later completed an MA and PhD in Creative Writing at Lancaster University. Between 2002 and 2006 she was a Centre Director for the Arvon Foundation.

Resources

Mami Wata

Smithsonian Institute description of the mermaid mythologies surrounding Mami Wata.

The Penguin Book of Mermaids: Highlights (video)

Discussion of The Penguin Book of Mermaids at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa by its authors, Cristina Bacchilega and Marie Alohalani Brown.

How Mermaid Stories Illustrate Complex Truths About Being Human

An excerpt from The Penguin Book of Mermaids on LitHub.

Merpeople: A Human History

By Vaughn Scribner (2020), published by Reaktion Books (Google Books preview).

‘The mermaid represents otherness, exile, blame, shame and beauty’ – An Interview with Monique Roffey

An interview with Roffey by Thom Cuell for Minor Literature[s].

About the Contributor

Diane Purkiss is Professor of English Literature at Oxford University, and is fellow, tutor, and director of studies in English at Keble College. She has published widely on gender and the supernatural, and on the English Civil War, and her book English Food: A People’s History was published by HarperCollins in November 2022. She is now working on a study of the English and their relationship with the sea.