‘The Little Black Boy’ by William Blake

The frontispiece from Life of William Blake by Alexander Gilchrist (1880), featuring an illustration of Blake after a portrait by John Linnell.

[Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons]

William Blake (1757–1827) was an English poet and painter producing art at a tumultuous time. Revolutions took place in America and France as well as in Great Britain’s manufacturing processes, creating political, industrial, and social upheaval. Radical world views, disillusionment, and religious imagery seeped into Blake’s work as artistic, literary, and intellectual movements transitioned from the Enlightenment to the Romantic era. Crucially, this was also the height of the transatlantic slave trade, in which Britain played a major role.

Despite William Blake’s work being dismissed as eccentric during his lifetime, Blake’s poem ‘London’ from his Songs of Experience collection (1794) is featured in GCSE anthologies, which attests to his legacy. In this poem, the narrator notes the ‘Marks of weakness/marks of woe’ etched on the faces of the people they meet as they ‘wander’ through the streets of eighteenth-century London. Here, Blake appears to be a radical champion of vulnerable people such as ‘Infants’, ‘Chimney-sweepers’ and ‘youthful Harlots’. Ed Simon describes Blake as being ‘influenced by non-conformist religious sects … which compelled him to reject slavery as an abject horror’. But in other work, such as ‘The Little Black Boy’ in his Songs of Innocence collection (1789), Blake’s standpoint is difficult to accept. Such contradictions are alluded to in the subtitle of his collections which refer to the poems as expressing ‘the two contrary states of the human soul’.

The poem for this week’s extract, explicitly marks racialised religious symbolism onto the skin and souls of children to explore the vulnerable position of the title’s narrator (a little black boy), who is keenly aware of the conflation of black with evil and white with good. Binary oppositions which were used to justify slavery and condemn black people are reinforced and embedded throughout the poem.

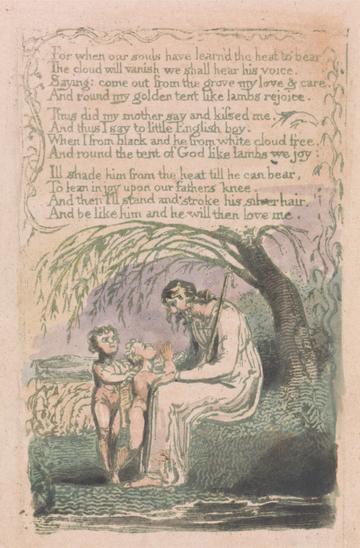

Print of the final page of ‘The Little Black Boy’ from Songs of Innocence and of Experience by William Blake

[Public Domain via the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection]

Whilst Blake’s countrymen enslaved and transported African people, the poem speaks of the child’s birthplace as the ‘southern wild’, alluding to Africa and its people as savage and uncivilised. The antithetical second line: ‘And I am black, but O! my soul is white’, exposes his black skin as ‘a cloud, and like a shady grove’ which shields the child’s ‘white’ soul. An exclamatory caesura ‘O!’ expresses his sadness and the hardship of his earthly position existing as a black boy. The ‘English child’, by contrast, is ‘White as an angel’. Radically, we never hear the voice of the English boy, yet his innocent, pure, virtuous status is emphasised. Conversely, the African boy is ‘bereav’d of light’. It appears that, in life, his black skin is associated with death, loss and grief.

The early years of the narrator’s religious education taught him that ‘these black bodies and this sun-burnt face’ is an earthly barrier until ‘our souls have learn’d the heat to bear’. Later in the poem, he reassures the ‘little English boy’ that because of the worldly suffering he has endured as a black boy on earth he is now equipped to ‘shade him from the heat’. The little white boy has not been forced to endure any hardships; therefore, the little black boy offers to protect him until he has learned ‘to lean in joy upon our father’s knee’.

In heaven, ‘When I from black and he from white cloud free’, the narrator acknowledges that both little boys will be free of their earthly skin which has created a barrier. In death, moreover, the little black boy notes that he will be loved by the white boy: ‘I’ll … be like him and he will then love me’. This suggests that the English boy can only love what is like him – an indictment indeed for a Christian child who should love neighbour and strangers alike – leaving us to wonder if it is only in death (when the little black boy’s white soul is revealed) that he can ‘then’ be loved?

When exploring a writer’s work, it’s important to consider a range of poems rather than a single piece, and to reckon with any problematic aspects we might find. There are important conversations to be had when we truly confront a canon, examining it in its complexity and asking how it has shaped the world we inhabit. This is why engaging with a poem like ‘The Little Black Boy’ is relevant today.

As Blake’s poetry continues to be taught and remains an important part of the English literary canon, the devastating question and Blakeian legacy I am confronted with as a woman of colour reading this poem is: do the depths of these racialised ideas etched onto the child’s black skin continue to be ascribed to my own skin? To consider this question and investigate the poem further, I would encourage you to read the poem and explore the themes below.

—Wendy Lennon

The Little Black Boy

My mother bore me in the southern wild,

And I am black, but O! my soul is white;

White as an angel is the English child:

But I am black as if bereav’d of light.

My mother taught me underneath a tree

And sitting down before the heat of day,

She took me on her lap and kissed me,

And pointing to the east began to say.

Look on the rising sun: there God does live

And gives his light, and gives his heat away.

And flowers and trees and beasts and men receive

Comfort in morning joy in the noonday.

And we are put on earth a little space,

That we may learn to bear the beams of love,

And these black bodies and this sun-burnt face

Is but a cloud, and like a shady grove.

For when our souls have learn’d the heat to bear

The cloud will vanish we shall hear his voice.

Saying: come out from the grove my love & care,

And round my golden tent like lambs rejoice.

Thus did my mother say and kissed me,

And thus I say to little English boy.

When I from black and he from white cloud free,

And round the tent of God like lambs we joy:

Ill shade him from the heat till he can bear,

To lean in joy upon our father’s knee.

And then I’ll stand and stroke his silver hair,

And be like him and he will then love me.

Some themes and questions to consider

-

How does this poem fit into the canon of such a revered English poet? How does it compare to any other Blake poems you know?

-

Do you think the poem is critical of the racial hierarchy that it describes?

-

How do you think Blake’s contemporary readers would have understood this poem?

-

How does Blake present religion in his poetry?

-

Compare the ways Blake presents ideas about power in ‘London’ and in one other Blake poem.

Full text

The full text of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience is available via Project Gutenberg.

Resources

Great Writers Inspire: William Blake

A set of open-access multimedia resources on Blake at Oxford’s Great Writers Inspire.

The William Blake Archive

An incredibly rich international resource on everything Blake.

British Library: William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience

A helpful brief overview of the collection by the British Library.

William Blake, Radical Abolitionist

Article by Ed Simon for JSTOR Daily.

Connections

If you’re looking for a longer reading experience you could compare this text to abolitionist writing by black authors that we have featured in Ten-Minute Book Club:

- The Interesting Narrative by Olaudah Equiano (published in the same year as Blake’s Songs of Innocence, 1789)

- The History of Mary Prince by Mary Prince

- The poems of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

You might also find it interesting to read this text alongside the extract from The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois, which was our first Ten-Minute Book Club entry. There, Du Bois talks about ‘double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.’

About the Contributor

Wendy Lennon is a doctoral researcher at the Shakespeare Institute working across history, literature, and race. She founded the international ‘Shakespeare, Race & Pedagogy’ education initiative in 2019, and project managed an ERC-funded program at the University of Oxford which received the 2022 Vice-Chancellor’s Innovation and Engagement award. Her first academic book, Shakespeare, Race & Pedagogy: Early Modern Colonialism to the Windrush is to be published by Cambridge University Press in 2023 and she has a chapter titled ‘Skin/Pedagogy’ forthcoming in an Arden Bloomsbury collection. Lennon reviews for the journal Shakespeare and the TLS, amongst others. She is a member of the BSA’s education committee, a Fellow of the English Association and is on the editorial board for the journal English. Following her undergraduate English degree at Royal Holloway, University of London and University of Exeter PGCE, Wendy was an English teacher for a decade.