‘The Cock and the Jasp’ from Morall Fabillis by Robert Henryson

Aesop’s Fables are often thought of as meant for children, using a story about animals to teach and explain a moral lesson. This text, from fifteenth-century courtly Scotland and written by Robert Henryson in Middle Scots, shows a very different way of thinking about what a fable is, how it might be read, and how Aesop’s wisdoms were repurposed in each age as they travelled across geographical and cultural distances.

In this fable, a cock finds a jewel in a dung heap whilst scratching for food. Reasoning that the jewel is of no use to him (and vice versa), the cock leaves it behind, preferring the simple nourishment of corn and chaff.

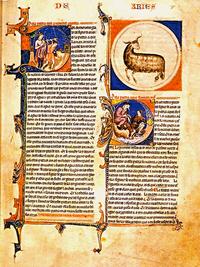

To understand the odd moral of this fable, it helps to know that medieval wisdom held that jewels and crystals had particular ‘virtues’ or powers. These properties were listed in lapidaries (books of stones) such as the famous Lapidary of King Alfonso X of Castile (‘Alfonso the Learned’) that drew on the wisdom of the population of Christian, Jewish and Muslim scholars in thirteenth-century Castile. The ‘jasp’ the cock finds would be a piece of a group of semi-precious stones known as chalcedony, a group which includes agate, jasper, and carnelian, and would have been a typical material for a carved cameo or seal. The cock recognises that he’s found something valuable, and addresses the stone directly, but leaves it in the rubbish heap because he cannot eat a jewel and he is hungry. Bad luck for the stone, and, as we later learn, the cock apparently misses out on its powers of good luck, protection and wisdom. The moral of the fable even directly references the well-known idiom ‘like pearl before swine’, derived from the biblical verse Matthew 7:6, which suggests that giving something valuable to those who don’t understand that value is a waste.

But before we are too quick to swallow the prescribed lesson, it’s worth thinking about how surprising this moral is: would it really have been the best choice for the cock to ignore his daily search for food in order to keep a gem? In fact, other fables in Henryson’s collection warn against being distracted by riches, like ‘The Two Mice’: (‘Blissid be sempill lyfe’ [Blessed be simple life]). And another writer, John Lydgate, appends the exact opposite of this moral to his version of this fable from 1410, praising the cock for his practical mindset. Lapidaries sometimes contain descriptions of ideal owners of jewels, so the cock is not without contemporary support in suggesting that he is not the right match.

This fable gives us other clues that something more is going on here than meets the eye. There’s a traditional distinction between fable and moral, or story and lesson, which can lead us to expect for the story to be fun and the lesson that follows to be a straight (possibly boring!) explanation. In medieval tradition these morals were usually written in brief epigrams or prose to mark them out as a commentary on the text. But Henryson’s moral is almost as long as the tale itself and it’s written in the same verse form (rime royal). The effect is that the distinction between fable and moral is blurred. When a poem presents itself as being self-interpreting, we can either take the interpretation we’re given as authoritative or we can treat the moral itself as a literary device in tension with the rest of the poem that needs our interpretation as well. This is why A. C. Spearing has described ‘The Cock and the Jasp’ as an ‘allegory of allegorical interpretation’: it is a fable that invites us to think again about how we interpret fables.

The basic premise of the fable genre, that the behaviour of others (usually animals) can be a metaphor for human ethics, is explored by Henryson in the Prologue to this text:

the caus quhy that thay first began

Wes to repreif thee of thi misleving,

O man, be figure of ane uther thing

The cause why [fables] first began

was to reprieve you of your bad behaviour,

O Man, through the symbols of other things.

Henryson implies an aura of ancient wisdom to these stories, but his revision of these texts is for readers contemporary to him. Writing commentaries on these ancient secular texts was an established tradition by the fifteenth century, so Henryson breaks a number of conventions, including quietly incorporating stories from the mischievous exploits of Reynard the Fox! Henryson’s intricately versified collection, which elaborates on what were usually short fables, suggests that he’s drawing our attention not to one simple meaning, but to the literary mechanisms through which that meaning is created, perhaps inviting us to look again.

—Alexandra Paddock

The Cock and the Jasp

Ane cok sumtyme with feddram fresch and gay,

Richt cant and crous albeit he was bot pure,

Flew furth upon ane dunghill sone be day.

To get his dennar set was al his cure.

Scraipand amang the as be aventure

He fand ane jolie jasp richt precious

Wes castin furth in sweping of the hous.

As damisellis wantoun and insolent

That fane wald play and on the streit be sene,

To swoping of the hous thay tak na tent

Quhat be thairin swa that the flure be clene,

Jowellis ar tint as oftymis hes bene sene

Upon the flure and swopit furth anone.

Peradventure sa wes the samin stone.

Sa mervelland upon the stane, quod he,

“O gentill jasp, O riche and nobill thing,

Thocht I thee find, thow ganis not for me.

Thow art ane jowell for ane lord or king.

It wer pietie thow suld in this mydding

Be buryit thus amang this muke and mold

And thow so fair and worth sa mekill gold.

“It is pietie I suld thee find for quhy

Thy grit vertew nor yit thy cullour cleir

I may nouther extoll nor magnify,

And thow to me may mak bot lyttill cheir,

To grit lordis thocht thow be leif and deir.

I lufe fer better thing of les availl

As draf or corne to fill my tume intraill.

“I had lever ga skraip heir with my naillis

Amangis this mow and luke my lifys fude

As draf or corne, small wormis or snaillis,

Or ony meit wald do my stomok gude

Than of jaspis ane mekill multitude,

And thow agane upon the samin wyis

May me as now for thin availl dispyis.

“Thow hes na corne and thairof I had neid.

Thy cullour dois bot confort to the sicht

And that is not aneuch my wame to feid

For wyfis sayis that lukand werk is licht.

I wald sum meit have, get it geve I micht,

For houngrie men may not weil leif on lukis.

Had I dry breid, I compt not for na cukis.

“Quhar suld thow mak thy habitatioun,

Quhar suld thow dwell bot in ane royall tour,

Quhar suld thow sit bot on ane kingis croun,

Exaltit in worschip and in grit honour?

Rise, gentill jasp, of all stanis the flour,

Out of this fen and pas quhar thow suld be.

Thow ganis not for me nor I for thee.”

Levand this jowell law upon the ground

To seik his meit this cok his wayis went;

Bot quhen or how or quhome be it wes found

As now I set to hald na argument,

Bot of the inward sentence and intent

Of this fabill as myne author dois write

I sall reheirs in rude and hamelie dite.

Moralitas

This jolie jasp hes properteis sevin.

The first, of cullour it is mervelous,

Part lyke the fyre and part is lyke the hevin.

It makis ane man stark and victorious,

Preservis als fra cacis perrillous.

Quha hes this stane sall have gude hap to speid.

Of fyre nor fallis him neidis not to dreid.

This gentill jasp richt different of hew

Betakinnis perfite prudence and cunning

Ornate with mony deidis of vertew

Mair excellent than ony eirthly thing,

Quhilk makis men in honour ay to ring,

Happie and stark to haif the victorie

Of all vicis and spirituall enemie.

Quha may be hardie, riche, and gratious?

Quha can eschew perrell and aventure?

Quha can governe ane realme, cietie, or hous?

Without science, no man, I yow assure.

It is riches that ever sall indure

Quhilk maith nor moist nor uther rust can freit.

To mannis saull it is eternall meit.

This cok, desyrand mair the sempill corne

Than ony jasp, may till ane fule be peir

Makand at science bot ane knak and scorne

And na gude can, als lytill will he leir.

His hart wammillis wyse argumentis to heir

As dois ane sow to quhome men for the nanis

In hir draf troich wald saw the precious stanis.

Quha is enemie to science and cunning

Bot ignorants that understandis nocht

Quhilk is sa nobill, precious, and ding

That it may with na eirdlie thing be bocht.

Weill wer that man over all uther that mocht

All his lyfe dayis in perfite studie wair

To get science for him neidit na mair.

Bot now allace this jasp is tynt and hid.

We seik it nocht nor preis it for to find.

Haif we richis, na better lyfe we bid,

Of science thocht the saull be bair and blind.

Of this mater to speik, it wair bot wind,

Thairfore I ceis and will na forther say.

Ga seik the jasp quha will for thair it lay.

The Tale

Once a cock with plumage fresh and gay,

Very lively and bold though he was poor,

Flew forth onto a dunghill at break of day.

To get his dinner was his only plan.

Scraping among the ashes, by accident

He found a brilliant jasp so precious

Had been cast out during sweeping of the house.

As careless and insolent maidservants

Who would rather play and in the street be seen

When sweeping the house take no notice

Of what might be there, save if the floor is clean,

So jewels are lost as often has been seen

Upon the floor and swept out at once.

By accident so was this same stone.

So marvelling at the stone, said he

“Oh excellent jasp, oh rich and noble thing,

Though I found thee; you are of no use to me

Thou are a jewel for a lord or king.

It would be a pity should you in this midding [compost]

Be buried thus among this muck and soil

When you are beautiful and worth so much gold.

“It is a pity I should find you because

Your great power nor your bright colour

I can neither exalt nor glorify,

And you to me can make but little feast,

To great lords’ thoughts you are precious and dear.

I love far better something of less value

Such as malt or grain to fill my empty guts.

“I had rather go scrape here with my claws;

Among this dust and seek my life’s food

Such as malt or grain, small worms or snails,

Or any food that would do my stomach more good

Than of jasps a great multitude,

And you again in the same fashion

Might despise me now for your fate.

“You have no corn and [if] I had need thereof;

Your colour does comfort only to the sight

And that is not enough to feed my belly

For women say that the act of looking is light.

I would have some food if I might get it;

For hungry men may not live well on looks;

If I had dry bread, I would care for no cooks.

Where should you make your habitation,

Where should you dwell but in a royal tower

Where should you sit but on a king’s crown

Exalted in worship and in great honour?

Rise, gentle jasp, of all stones the flower

Out of this fen and go where you should be

Thou are of no use to me nor I to thee.”

Leaving this jewel low on the ground

To seek his food this cock went on his way

But when or how or by whom it was found

As now intend to carry on no debate

But of the inner meaning and intent

Of this fable as my author does write

I shall rehearse in rough and homely style.

The Moral

This brilliant jasp has properties seven

The first, in colour it is marvellous,

Partly like fire and partly like heaven,

It makes a man mighty and victorious,

Protected also from destinies dangerous.

Whoever has this stone shall have good luck to spare.

Of fire nor falls he needs to have no fear.

This noble jasp is well varied of hue

Signifying perfect prudence and cunning

Ornate with many deeds of virtue

More excellent than any earthly thing,

Which makes men in honour always to reign,

Happy and strong to have victory

Over all vices and spiritual enemy.

Who can be hardy, rich and generous?

Who can avoid peril and danger?

Who can govern a realm, city or house?

Without knowledge, no man, I you assure.

It is riches that ever shall endure

Which maggots nor damp nor other rust can chew

To men’s souls it is eternal food.

This cock, desiring more the simple corn

Than any jasp, to a fool might compare

Making of knowledge merely a knock and scorn

And can do no good, and as little will he learn

His heart sickens wise arguments to hear,

As does a sow to whom men, for example,

In her swill trough might cast precious stones.

Who is enemy to learning and wisdom

But ignorant people who understand not

Which thing is so noble, precious, and exalted

That it may with no earthly thing be bought.

Favoured would be that man over others who could

All his life’s days in perfect studying lead

To gain knowledge: for him there is no other need.

But now alas this jasp is lost and hidden

We seek it not nor hasten to find it.

If we have riches, we aspire to no better life

Though of wisdom the soul is bare and blind.

But speaking of this matter is blowing in the wind,

Therefore I stop and nothing more say

Go seek the jasp, whoever wishes, for there it lay.

Some themes and questions to consider

-

Wisdom: how do we seek wisdom? And is a “dunghill” the best place to look?

-

Environment: what imagining of the animal views of the world are offered through these fables?

-

Why did the chicken cross the road…: why is it so compelling to think of chicken-kind taking an interest in human concerns, and vice versa?

Full text

Read the full text of Henryson’s Fables in the original Older Scots, with glossary and introduction at the University of Rochester’s Middle English Texts Series.

Connections

If you’re looking for a longer reading experience you could bring this text alongside the Exeter Book riddles from this season, which are another genre of literature that explicitly asks for interpretation.

The Author

Very few biographical details are known about the author of this text, Robert Henryson. The earliest manuscripts and prints of Henryson’s poems are dated well after his lifetime, especially in the case of the Fables as well as The Testament of Cresseid. William Dunbar, Scots poet, writes about Henryson’s death in Dumferline. Many of the sixteenth-century printers of his works, including William Caxton, refer to him as Maister Henryson, suggestion that he may have been a schoolmaster, or clerk of some kind. In 1462 a Robert Henryson graduated as Master of Arts and Bachelor of canon law at the newly founded (1451) University of Glasgow: this may have been our author.

For more on the Henryson’s life, see David Parkinson’s introduction where he explains:

Following [the scraps of available evidence], one glimpses a Henryson born about 1430 and dead by about 1500 who was a scholar in the arts and law, who worked as a notary public and schoolmaster in late fifteenth-century Dunfermline, a royal burgh on the north shore of the Firth of Forth. His home was a Scottish town of no great size but nevertheless distinguished by its Benedictine abbey, a resting place of kings and queens, among them Robert the Bruce and St. Margaret of Scotland.

Form

This poetic collection of Fables is composed in a verse form called ‘rhyme royal’ or ‘rime royal’, a seven-line stanzaic form in iambic pentameter that rhymes ababbcc. This verse form gets its name from its use in The Kingis Quair (The King’s Book), a poem attributed to James I of Scotland describing his capture by the English in 1406. Rhyme royal is considered to be an innovation of Geoffrey Chaucer, towards the end of the fourteenth century. Chaucer’s work was read and admired by the fifteenth-century Scots makars, and was often explicitly referenced by them. Henryson even wrote a sequel to Chaucer’s tragic Trojan love poem, Troilus and Criseyde, called the Testament of Cresseid. The reverence with which the poets who followed Chaucer treated his work may have contributed to the idea of him as the ‘Father’ of English, by poets who consistently depicted themselves as his successors.

Middle Scots Language

Henryson’s work was important in establishing Scots as a literary language. Spoken in middle-class urban contexts in late medieval Scotland, this language shares fundamental structures with English, but is distinctively different in almost every aspect. The rhymes that Henryson uses here give us clues to how the vowels should be pronounced. There are other features to look out for like the use of <quh-> for <wh->, so quha, quhair, quhen instead of who, where, when. In Middle Scots, modern English pronouns like scho, thay, thaim, thair, are used earlier than in southern versions of Middle English.

Find out more about Middle Scots.

Resources

Scottish Poetry Library

Read the entry on Robert Henryson.

Great Writers Inspire: Fables

A set of open access resources on fables.

Lapidaries Rock: Medieval Books on Gems, Stones, and Minerals

On the medieval tradition of lapidaries and magic stones see academic Erik Kwakkel’s website and blog Medieval Fragments.

Thomas F. Glick, Steven J. Livesey, and Faith Wallis. Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia (2005)

Read more about medieval science and how it is linked to medieval literature in this Google Books preview.

About the Contributor

Dr Alexandra Paddock is Lecturer in Old and Middle English at Keble College, Oxford, and is also the Project Lead on Ten-Minute Book Club. In her research she has a particular focus on animals and nature taxonomies. Published and forthcoming work includes work on digging creatures in the bestiary and medieval riddles, the elephant of Henry III, and submerged bodies in the landscape in medieval poetry. Her current book project Unland looks at animal-spatial metaphors in medieval literature. Alongside medieval literature she also writes and teaches on animal presence and other minds in nineteenth-century literature, fairy tale and children’s literature and modern anglophone theatre, including a co-published Oxford bibliography on Elizabeth Robins.